South Korea

Seitenübersicht

[Ausblenden]- 1 General Information

- 1.1 Preparedness and Planning

- 1.1.1 Law and Administration

- 1.1.2 Healthcare

- 1.1 Preparedness and Planning

- 2 Sense Making

- 3 Decision Making and Coordinating

- 4 Meaning Making, Crisis Communication and Legitimacy

- 5 Comparison

- 6 Overall evaluation following the crisis management literature

- 7 Stay at home songs

- 8 References

South Korea is a highly developed country in South-East Asia, that was well prepared for a Pandemic like Covid-19, both in planning, partly through prior experience, and in healthcare. After a couple of weeks with a small number of cases, a big outbreak emerged in Daegu mid-February that was brought under control successfully with the country’s signature 3T (test, trace, treat) approach, that utilizes highly digitalized tools and collaborative approaches as well as massive testing and smart patient management to avoid large scale lockdowns as much as possible.

Various social distancing measures were introduced, though mostly in the form of recommendations, with outcomes widely considered successful.

The government reacted quickly, taking Covid-19 very seriously from the start, employing examplary crisis communication which has brought the government large amounts of support which could be seen in the latest national election, after mediocre approval ratings before the crisis.

Various social distancing measures were introduced, though mostly in the form of recommendations, with outcomes widely considered successful.

The government reacted quickly, taking Covid-19 very seriously from the start, employing examplary crisis communication which has brought the government large amounts of support which could be seen in the latest national election, after mediocre approval ratings before the crisis.

1 General Information

South Korea, formally the Republic of Korea, is a country in East Asia with a very homogenous population of around 51 million people. (KOSIS 2018)

South Korea is one of the most urbanized countries in the world, with 81.6% of people living in urban environments (worldometer 2020) and an average population density of 509.2 people per sq. km (KOSIS 2018), one of the highest in the world, but still underrepresenting the population density the average Korean lives in, since large parts of the country are uninhabitable due to geographical features and agriculture. (CIA 2019)

The birthrate is one of the lowest worldwide, making South Korea age fast. (World Bank 2019) Currently 14% of the population are 65+ with the bulk of the population being middle aged, which is almost double the worlds average but only about two thirds of the percentage common in many Western European countries. (World Bank 2018)

The economy is highly developed, with a strong focus on technology and considered very innovative. (GlobalEdge 2020)

South Korea is a presidential democracy, currently headed by Moon Jae-in of the liberal Democratic Party. (Kwon, Boykoff and Griffiths 2017) Ministers are appointed by the President on recommendation of the Prime Minister, who is appointed by the president with parliamentary consent and reports to the Prime Minister who acts as a kind of buffer between the state council and the president. (CIA 2019; KOCIS 2020b)

There are two levels of local government in South Korea, a higher level which consists of 17 provinces and metropolitan areas and a lower level consisting of 226 smaller cities, counties and districts. (KOCIS 2020a) These local governments have only limited ability to make policy themselves, their main task is to decide on the specifics of implementation of national law. (Pike 2018)

South Korea is one of the most urbanized countries in the world, with 81.6% of people living in urban environments (worldometer 2020) and an average population density of 509.2 people per sq. km (KOSIS 2018), one of the highest in the world, but still underrepresenting the population density the average Korean lives in, since large parts of the country are uninhabitable due to geographical features and agriculture. (CIA 2019)

The birthrate is one of the lowest worldwide, making South Korea age fast. (World Bank 2019) Currently 14% of the population are 65+ with the bulk of the population being middle aged, which is almost double the worlds average but only about two thirds of the percentage common in many Western European countries. (World Bank 2018)

The economy is highly developed, with a strong focus on technology and considered very innovative. (GlobalEdge 2020)

South Korea is a presidential democracy, currently headed by Moon Jae-in of the liberal Democratic Party. (Kwon, Boykoff and Griffiths 2017) Ministers are appointed by the President on recommendation of the Prime Minister, who is appointed by the president with parliamentary consent and reports to the Prime Minister who acts as a kind of buffer between the state council and the president. (CIA 2019; KOCIS 2020b)

There are two levels of local government in South Korea, a higher level which consists of 17 provinces and metropolitan areas and a lower level consisting of 226 smaller cities, counties and districts. (KOCIS 2020a) These local governments have only limited ability to make policy themselves, their main task is to decide on the specifics of implementation of national law. (Pike 2018)

1.1 Preparedness and Planning

1.1.1 Law and Administration

All crisis management in South Korea starts from the Framework Act on the Management of Disasters and Safety, which outlines the responsibilities of all levels and divisions of government over every aspect of risk management. The act forces all levels of government to set up a Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarter for operational matters during a crisis, and local governments are required to develop a specific plan for infectious disease control. On the strategic level, there is the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act further specifying responsibilities, coordination and powers. (OECD 2020)

The central government agency for dealing with Sars-Cov-2 in South Korea is the Korean Center for Disease Control (KCDC). It is in charge of dealing with the primary outfall of any disease, this includes risk assessment, stockpiling, coordination, communication, disease surveillance and investigation as well as operational matters. It has seen its powers greatly enhanced over the past years, especially after the MERS-CoV outbreak in 2015, which has shown itself to be an important reference point for the Sars-Cov-2 Pandemic. (OECD 2020)

That year, "a South Korean businessman came down with Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) after returning from a visit to three Middle Eastern countries. He was treated at three South Korean health facilities before he was diagnosed with MERS and isolated. By then, he had set off a chain of transmission [largely in the hospital system] that infected 186 and killed 36, including many patients hospitalized for other ailments, visitors, and hospital staff. Tracing, testing, and quarantining nearly 17,000 people quashed the outbreak after 2 months. The specter of a runaway epidemic alarmed the nation[…]." (Normile 2020)

One big political issue at the time was the lacking communication and transparency of the details how the virus had spread and especially which hospitals were having outbreaks. (Thompson 2020)

The KCDC and other relevant governmental actors had and have gained some of the following powers, obligations and abilities (OECD 2020, 4.4)

Note: This is not a comprehensive list, but rather supposed to paint a good picture of the capabilities to deal with Covid-19 from an administrative perspective.

A four-level warning system is in place, ranging from Attention (Blue) over Caution (Yellow), Alert (Orange) to Serious (Red) or in the specific case of infectious disease: Disease outside the country, domestic cases reported, high probability of spread of an infectious disease and on-going spread of an infectious disease. (OECD 2020) New Zealand has a somewhat similar approach.

The central government agency for dealing with Sars-Cov-2 in South Korea is the Korean Center for Disease Control (KCDC). It is in charge of dealing with the primary outfall of any disease, this includes risk assessment, stockpiling, coordination, communication, disease surveillance and investigation as well as operational matters. It has seen its powers greatly enhanced over the past years, especially after the MERS-CoV outbreak in 2015, which has shown itself to be an important reference point for the Sars-Cov-2 Pandemic. (OECD 2020)

That year, "a South Korean businessman came down with Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) after returning from a visit to three Middle Eastern countries. He was treated at three South Korean health facilities before he was diagnosed with MERS and isolated. By then, he had set off a chain of transmission [largely in the hospital system] that infected 186 and killed 36, including many patients hospitalized for other ailments, visitors, and hospital staff. Tracing, testing, and quarantining nearly 17,000 people quashed the outbreak after 2 months. The specter of a runaway epidemic alarmed the nation[…]." (Normile 2020)

One big political issue at the time was the lacking communication and transparency of the details how the virus had spread and especially which hospitals were having outbreaks. (Thompson 2020)

The KCDC and other relevant governmental actors had and have gained some of the following powers, obligations and abilities (OECD 2020, 4.4)

- Extensive emergency response plans across all levels of government

- Establishment of the National Disaster Safety Control Center (NDSCC) which brings all relevant ministries and agencies together under the Prime Minister to strengthen coordination

- KCDC has developed its own Emergency Operation Center

- Partnerships with telecommunication and media companies to allow for broad, fast and effective transmission of warning messages.

- An App and Website called safemap that allows the government to show various information regarding any crisis and riskfactor, in the specific case it can be used to show the locations of testing facilities and places where personal protective equipment (PPE) such as masks are available.

- Access to GPS and Credit Card data as well as CCTV footage from places an infected person visited.

- A real-time-management system for emergency stockpiles, which include PPE.

- Hiring of a significant amount of infectious disease specialists of all sorts, from treatment to tracing as well as crisis communication experts.

- Specific quarantine stations and hospitals equipped with negative pressure rooms strategically placed throughout the country.

- Comprehensive simulation exercises for potential outbreaks, including stakeholders from the private sector and the citizenry. (CGTN 2020)

- The government is required by law to inform the citizens regularly and transparently during an outbreak.

Note: This is not a comprehensive list, but rather supposed to paint a good picture of the capabilities to deal with Covid-19 from an administrative perspective.

A four-level warning system is in place, ranging from Attention (Blue) over Caution (Yellow), Alert (Orange) to Serious (Red) or in the specific case of infectious disease: Disease outside the country, domestic cases reported, high probability of spread of an infectious disease and on-going spread of an infectious disease. (OECD 2020) New Zealand has a somewhat similar approach.

1.1.2 Healthcare

South Koreas health system is continuously rated as one of the best in the world, as it ranks 9th in GHS Index, with especially high scores in the Detect and Respond categories, that are crucial to fight an infectious disease. (GHS Index 2019)

South Koreans benefit from a universal public health insurance, with sometimes significant premiums and co-payments, for the latter of which private insurance exists. Citizens with low income a program is in place to cover these costs.

It is common in South Korea to go to the hospital first, as the primary health system consisting of general practitioners ("family doctors") is not strongly developed. There are public health centers, but it is not required to go to them first. (OECD 2020)

South Korea had 13.05 hospital beds per 1000 citizens in 2017, which is more than double the OECD average of 4.8 and 10.6 Intensive Care beds per 100.000 citizens. (OECD 2019)

South Koreans benefit from a universal public health insurance, with sometimes significant premiums and co-payments, for the latter of which private insurance exists. Citizens with low income a program is in place to cover these costs.

It is common in South Korea to go to the hospital first, as the primary health system consisting of general practitioners ("family doctors") is not strongly developed. There are public health centers, but it is not required to go to them first. (OECD 2020)

South Korea had 13.05 hospital beds per 1000 citizens in 2017, which is more than double the OECD average of 4.8 and 10.6 Intensive Care beds per 100.000 citizens. (OECD 2019)

2 Sense Making

The interactive charts to the right show the confirmed cases of and deaths due to Covid-19 in South Korea, as well as the Government Response Index, a measure of policy activity related to Covid-19 developed by the Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford. It combines ordinally scaled variables measuring policies about containment and closure, the economy and the health system, for a detailed explanation of the Index and its variables see here, its maximum value is 100.

Case and death data are scaled logarithmically for two reasons, first to allow for cumulative and daily data to meaningfully exist in the same chart and second, because it is better at displaying the potentially exponential growth rate a virus usually would show without adequate countermeasures.

A confirmed case in South Korea is anyone who has tested positive for the virus, with one of the approved PCR tests.

As of today, I have not been able to find information on the exact procedure of reporting cases or reporting and confirming deaths (likely also based on positive test results) in South Korea, but there has been no reason to doubt it is done in a timely and accurate manner.

Two groups of people are tested for Covid-19 (Kcdc 2020):

Until February 17 daily data on the number of tests is not available, therefore calculations for the 5-day rolling average of daily tests are not entirely accurate. These numbers include tests that have been taken but not yet examined.

As of June 25, 1,232,315 people have been tested, that equals around 2,39% of the South Korean population or approximately 1 in 50 people. Another important number to consider is the positivity rate, the number of tests per confirmed case, which can be used as a measure whether a country is testing enough to accurately depict its outbreak. The WHO suggests 10 tests per case or 10% to be desirable. (WHO 2020) For South Korea this number overall as of June 25 is 1,02% or ~100 per case and has been at least 20 on a daily basis for the entire duration of the outbreak.

The charts for cases and deaths split by age and gender show some interesting discrepancies: 57.28% of cases are female, but only 46.45 % of deaths. The age group of 20-29 are responsible for 26.32% of cases but only make up 13.18% of the population, for none of which comprehensive arguments to explain them exist at this point.

Two more statistics to consider when it comes to Covid-19 related deaths are the case fatality rate and excess mortality.

The total case fatality rate for South Korea as of June 25 is 2.24% and has been stable at that level for the entire relevant time of the pandemic. (Early case fatality rates are likely to have negative bias because it normally takes significant time until people die of Covid-19)

Excess mortality describes the deviation of deaths for a timeframe off the average for previous years, and therefore includes also deaths caused indirectly by the pandemic. The number of excess deaths from February to April compared to 2016-2019 is 3711,75 or 5,14% higher. This value is statistically significant at a 95% confidence level with a p-value of 0.9951.

The map-charts illustrate two points, first how large in relative scale the outbreak in Daegu related to Shincheonji was, and second how well that outbreak was contained and second that Seoul and its surrounding regions are now struggling with their outbreak.

For data and image sources see References:Data

.

Case and death data are scaled logarithmically for two reasons, first to allow for cumulative and daily data to meaningfully exist in the same chart and second, because it is better at displaying the potentially exponential growth rate a virus usually would show without adequate countermeasures.

A confirmed case in South Korea is anyone who has tested positive for the virus, with one of the approved PCR tests.

As of today, I have not been able to find information on the exact procedure of reporting cases or reporting and confirming deaths (likely also based on positive test results) in South Korea, but there has been no reason to doubt it is done in a timely and accurate manner.

Two groups of people are tested for Covid-19 (Kcdc 2020):

- Suspected case: A Person exhibiting fever (37.5 degrees or above) or respiratory symptoms (coughs, shortness of breath, etc.) within 14 days of contact with a confirmed COVID-19 patient during the confirmed patient’s symptom-exhibiting period.

- Patients Under Investigation (PUI):

- A person suspected of COVID-19 according to a physician’s opinion for reasons such as pneumonia of an unknown cause or the symptoms mentioned below.

- A person exhibiting fever (37.5 degrees or above) or respiratory symptoms (coughs, shortness of breath, etc.) within 14 days of entering Korea after visiting another country or with an epidemiological link to a domestic COVID-19 cluster.

Until February 17 daily data on the number of tests is not available, therefore calculations for the 5-day rolling average of daily tests are not entirely accurate. These numbers include tests that have been taken but not yet examined.

As of June 25, 1,232,315 people have been tested, that equals around 2,39% of the South Korean population or approximately 1 in 50 people. Another important number to consider is the positivity rate, the number of tests per confirmed case, which can be used as a measure whether a country is testing enough to accurately depict its outbreak. The WHO suggests 10 tests per case or 10% to be desirable. (WHO 2020) For South Korea this number overall as of June 25 is 1,02% or ~100 per case and has been at least 20 on a daily basis for the entire duration of the outbreak.

The charts for cases and deaths split by age and gender show some interesting discrepancies: 57.28% of cases are female, but only 46.45 % of deaths. The age group of 20-29 are responsible for 26.32% of cases but only make up 13.18% of the population, for none of which comprehensive arguments to explain them exist at this point.

Two more statistics to consider when it comes to Covid-19 related deaths are the case fatality rate and excess mortality.

The total case fatality rate for South Korea as of June 25 is 2.24% and has been stable at that level for the entire relevant time of the pandemic. (Early case fatality rates are likely to have negative bias because it normally takes significant time until people die of Covid-19)

Excess mortality describes the deviation of deaths for a timeframe off the average for previous years, and therefore includes also deaths caused indirectly by the pandemic. The number of excess deaths from February to April compared to 2016-2019 is 3711,75 or 5,14% higher. This value is statistically significant at a 95% confidence level with a p-value of 0.9951.

The map-charts illustrate two points, first how large in relative scale the outbreak in Daegu related to Shincheonji was, and second how well that outbreak was contained and second that Seoul and its surrounding regions are now struggling with their outbreak.

For data and image sources see References:Data

.

3 Decision Making and Coordinating

3.1 Timeline

3.2 Decision-making structure

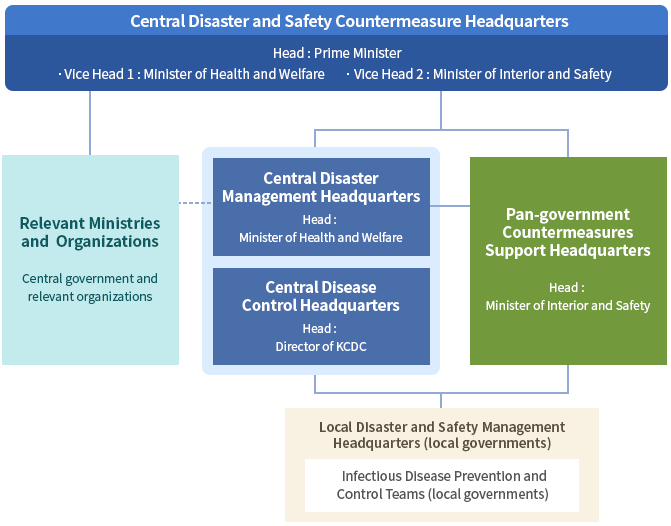

There are two main bodies responsible for dealing with Covid-19 in South Korea, the first one being the Central Disease Control Headquarters (CDCH) lead by the head of the KCDC which is responsible for infection prevention, control and treatment measures.

The second is the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (CDSCH) headed by the Prime Minister responsible for the overarching governmental response, coordinating efforts and supporting efforts by others.

Its first vice head is the Minister of Health and Welfare who is responsible for supporting CDCH as head of the Disaster Management Headquarters and its second vice head is the Minister of the Interior and Safety who is responsible for coordination and cooperation between local governments and the central ministries as head of the Pan-Government Countermeasures Support Headquarters. This structure is remarkable because the Minister of Health and Welfare who usually is the direct superior of the KCDC is put in the role of supporting the CDCH.

All local governments set up Local Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (each headed by its respective mayor or governor) to mobilize more infection prevention and control capabilities. Organizational units in charge of healthcare at local governments focus on infection prevention/control, while other organizational units support administrative and management tasks like the monitoring of those under self-isolation. (CDSCH 2020)

KCDC has four Covid-19 related operative departments: The Surveillance department, responsible for testing, the epidemiological investigation department for tracing, the management department overseeing isolation and sterilization and the educational department responsible for informing the public, helping the infected to get help from the proper agencies and coordinating with local governments. (Jeong et al. 2020)

Special management regions were set up in Daegu and Chengdu, as well as the neighboring Gyeongsan during the outbreak there and later Seoul and its surrounding provinces became a special management zone, where the more strict social distancing measures were kept, after their ease in the rest of the country. (The Straits Times 2020)

These regionally differentiated actions could be observed in many countries around the globe such as India, the Netherlands and Spain

The second is the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (CDSCH) headed by the Prime Minister responsible for the overarching governmental response, coordinating efforts and supporting efforts by others.

Its first vice head is the Minister of Health and Welfare who is responsible for supporting CDCH as head of the Disaster Management Headquarters and its second vice head is the Minister of the Interior and Safety who is responsible for coordination and cooperation between local governments and the central ministries as head of the Pan-Government Countermeasures Support Headquarters. This structure is remarkable because the Minister of Health and Welfare who usually is the direct superior of the KCDC is put in the role of supporting the CDCH.

All local governments set up Local Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (each headed by its respective mayor or governor) to mobilize more infection prevention and control capabilities. Organizational units in charge of healthcare at local governments focus on infection prevention/control, while other organizational units support administrative and management tasks like the monitoring of those under self-isolation. (CDSCH 2020)

KCDC has four Covid-19 related operative departments: The Surveillance department, responsible for testing, the epidemiological investigation department for tracing, the management department overseeing isolation and sterilization and the educational department responsible for informing the public, helping the infected to get help from the proper agencies and coordinating with local governments. (Jeong et al. 2020)

Special management regions were set up in Daegu and Chengdu, as well as the neighboring Gyeongsan during the outbreak there and later Seoul and its surrounding provinces became a special management zone, where the more strict social distancing measures were kept, after their ease in the rest of the country. (The Straits Times 2020)

These regionally differentiated actions could be observed in many countries around the globe such as India, the Netherlands and Spain

3.3 Legislative Reaction

Most of the law for the South Korean crisis response was already made in the aftermath of the MERS outbreak, however some adjustments of the legal frame were made on February 26 (Jeong et al. 2020; National Assembly Korea 2020):

- Amendment to the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act to allow for higher punishments if hospitalizations or quarantine measures are violated. Potential imprisonment up to 1 year or fines up to 10 million won (~7,900 USD). Further the changes empower the Minster of Health and Welfare, to take actions to secure and provide medical products and increase the number of epidemiological investigators and quarantine officers from 30 to 100. Local officials were given the authority to appoint epidemiological investigators and quarantine officials themselves.

- The Quarantine Act, to better fit an infectious viral disease like Covid-19 in particular to allow for the connection of databases containing information on the quarantined, passports and immigrants, and better integrate airports into the governmental reaction.

- Medical law to create an infection monitoring system for patients, guardians, and medical workers.

3.4 The 3T Strategy

The main strategy of the South Korean government to control Covid-19 consists of three steps: testing, tracing, and treating, aimed at containing the virus as quickly as possible.

3.4.1 Testing

Getting a test is free if one is a suspected case or person under investigation (for definitions see Sense Making) or available for 125 USD with the fee reimbursable through the healthcare system. This includes undocumented foreigners, who do not have to fear deportation when getting tested. (Lee and Lee 2020)

A crucial development to allow for the large amount of testing in South Korea were the drive-through and later walk-through screening centers, an idea which was later “exported” around the world.

Drive through testing was first suggested by the medical community in South Korea and pushed for by a provincial governor on Feb 23 in the structure described above to reduce the use of Personal Protective equipment, increase the space between the waiting people and protect workers. (Lee and Lee 2020)

The system works in three steps: registration, symptom check and sampling.

The first is usually done by administrative personnel who check the reservation (one has to register online before attending), educate the people and manage the cars and, if necessary, who exits their car. Doctors then conduct the symptom checks and sampling. Very early on this was done in containers, which required for disinfection every time, then the switch to tents was made which allowed people to stay in their cars. This cut the time per test down to around 10 minutes.

In more urban areas, where private vehicles and large amounts of space are less common, walk-through centers proved to be more effective. There are two variants, one where the medical professional is outside the booth with negative pressure, this has the disadvantage that the booth has to be disinfected each time, therefore a new system was developed, where the doctor is inside the booth and does the sampling with long gloves, requiring only those to be disinfected which cut the time per test down even further. (Lee and Lee 2020)

These screening stations are usually placed in the parking lots of hospitals, public health centers and government buildings, with the important function to keep potentially infected people away from hospitals and public health centers where especially vulnerable groups are likely to be. They are distributed widely across South Korea. (Lee and Lee 2020)

A crucial development to allow for the large amount of testing in South Korea were the drive-through and later walk-through screening centers, an idea which was later “exported” around the world.

Drive through testing was first suggested by the medical community in South Korea and pushed for by a provincial governor on Feb 23 in the structure described above to reduce the use of Personal Protective equipment, increase the space between the waiting people and protect workers. (Lee and Lee 2020)

The system works in three steps: registration, symptom check and sampling.

The first is usually done by administrative personnel who check the reservation (one has to register online before attending), educate the people and manage the cars and, if necessary, who exits their car. Doctors then conduct the symptom checks and sampling. Very early on this was done in containers, which required for disinfection every time, then the switch to tents was made which allowed people to stay in their cars. This cut the time per test down to around 10 minutes.

In more urban areas, where private vehicles and large amounts of space are less common, walk-through centers proved to be more effective. There are two variants, one where the medical professional is outside the booth with negative pressure, this has the disadvantage that the booth has to be disinfected each time, therefore a new system was developed, where the doctor is inside the booth and does the sampling with long gloves, requiring only those to be disinfected which cut the time per test down even further. (Lee and Lee 2020)

These screening stations are usually placed in the parking lots of hospitals, public health centers and government buildings, with the important function to keep potentially infected people away from hospitals and public health centers where especially vulnerable groups are likely to be. They are distributed widely across South Korea. (Lee and Lee 2020)

3.4.2 Tracing

Tracing has been the central point of the South Korean response and is largely attributed for the country’s success. To achieve this, South Korea relied on strong digital tools, backed up by the comprehensive legal toolkit described under Preparedness.

The investigators from the KCDC “use interviews, mobile phone tracking (every mobile account in South Korea is tied to the owner's national ID), credit card transaction history, and video footage from public surveillance cameras, to reconstruct the individual movements of confirmed COVID-19 cases in fine detail. They can also find or cross-check other people whom the patient had close contact with, prior to quarantine. Through manual effort, these officials can identify potential future cases, and target those people or areas for testing and precautionary self-quarantine”. (Lee and Lee 2020) This data is made public on the website of KCDC daily, stripped of direct personal information. The detailed itineraries and disclosure of workplaces (which is done if the person is likely to have had contact with a significant number of not-traceable people there) has in some cases lead to the identities of the patients being uncovered. In other cases, the patients were shamed for the places they visited. (BBC 2020)

As case numbers grew this system was not feasible for every case. In response the ministry of Infrastructure, the ministry of Science and ICT and the KCDC developed the Epidemiological Support System to partly automate this process by combining Data from the National Police Agency, the three major telecommunication firms and 22 credit card companies in a system that was designed for smart cities and adapted to this purpose. It was launched on March 26. Prior to this system this data had to be manually collected through telephone calls by the investigators, often through intermediaries. The system reduced the time per case spent on contact tracing drastically. It is only applied after patients are informed and is subject to comprehensive scrutiny against misuse. (Lee and Lee 2020)

Classified as a contact is generally anyone who had contact with the patient 24h before symptoms are shown or after. The final decision is made by local governments based on multiple factors like, if the patient wore a mask, the specific situation of contact etc. (Jeong et al. 2020)

Contacts identified through the epidemiological investigations are classified as Suspected Cases and therefore tested for COVID-19 and then either treated or put under self-quarantine and monitored on a one-on-one basis by assigned public health officials through an app equal to the one incoming travelers must use (see below), or via telephone. (Lee and Lee 2020)

The investigators from the KCDC “use interviews, mobile phone tracking (every mobile account in South Korea is tied to the owner's national ID), credit card transaction history, and video footage from public surveillance cameras, to reconstruct the individual movements of confirmed COVID-19 cases in fine detail. They can also find or cross-check other people whom the patient had close contact with, prior to quarantine. Through manual effort, these officials can identify potential future cases, and target those people or areas for testing and precautionary self-quarantine”. (Lee and Lee 2020) This data is made public on the website of KCDC daily, stripped of direct personal information. The detailed itineraries and disclosure of workplaces (which is done if the person is likely to have had contact with a significant number of not-traceable people there) has in some cases lead to the identities of the patients being uncovered. In other cases, the patients were shamed for the places they visited. (BBC 2020)

As case numbers grew this system was not feasible for every case. In response the ministry of Infrastructure, the ministry of Science and ICT and the KCDC developed the Epidemiological Support System to partly automate this process by combining Data from the National Police Agency, the three major telecommunication firms and 22 credit card companies in a system that was designed for smart cities and adapted to this purpose. It was launched on March 26. Prior to this system this data had to be manually collected through telephone calls by the investigators, often through intermediaries. The system reduced the time per case spent on contact tracing drastically. It is only applied after patients are informed and is subject to comprehensive scrutiny against misuse. (Lee and Lee 2020)

Classified as a contact is generally anyone who had contact with the patient 24h before symptoms are shown or after. The final decision is made by local governments based on multiple factors like, if the patient wore a mask, the specific situation of contact etc. (Jeong et al. 2020)

Contacts identified through the epidemiological investigations are classified as Suspected Cases and therefore tested for COVID-19 and then either treated or put under self-quarantine and monitored on a one-on-one basis by assigned public health officials through an app equal to the one incoming travelers must use (see below), or via telephone. (Lee and Lee 2020)

3.4.3 Treating

Patients are isolated differently depending on the severity of their symptoms. Asymptomatic cases are allowed to self-quarantine, if they are capable of independent living (which includes having a permanent residence) and do not live with somebody in a high-risk group. The next level is facility isolation in so called “life care centers” for people with mild symptoms, here their health status is monitored twice daily. These “life care centers” are usually repurposed lodging or government facilities. The final level is hospital isolation for people with moderate or severe symptoms. People may be transferred between these stages.

Trained professionals are dispatched to where they are most needed with support of the government. (CDSCH 2020; Jeong et al. 2020)

Around 70 hospitals were designated, to exclusively deal with Covid-19 patients, whilst 174 hospitals were designated as “Public relief hospitals” where outpatient and hospitalized treatment is fully separated from the treatment of respiratory patients to reduce the possibility of infection in hospitals and reduce potential reluctance of the usual patients from visiting hospitals. (Jeong et al. 2020) A similar approach has been followed in Portugal

Isolation is released after three weeks of symptoms are improved, or if two consecutive PCR-tests, 24h apart, are negative. For high risk patients both criteria must apply. (Jeong et al. 2020)

Trained professionals are dispatched to where they are most needed with support of the government. (CDSCH 2020; Jeong et al. 2020)

Around 70 hospitals were designated, to exclusively deal with Covid-19 patients, whilst 174 hospitals were designated as “Public relief hospitals” where outpatient and hospitalized treatment is fully separated from the treatment of respiratory patients to reduce the possibility of infection in hospitals and reduce potential reluctance of the usual patients from visiting hospitals. (Jeong et al. 2020) A similar approach has been followed in Portugal

Isolation is released after three weeks of symptoms are improved, or if two consecutive PCR-tests, 24h apart, are negative. For high risk patients both criteria must apply. (Jeong et al. 2020)

3.5 Open Data, Collaborative Arrangements and using ICT

Open Data has been an important part of South Koreas crisis communication. It enabled private developers to give convenient access to data simply provided in text form by the government.

The most prolific examples of this are apps like Corona 100m which alerts the user if he or she comes into proximity of the path of confirmed patients or services like coronamap (link) which show the places confirmed patients visited on a map. Other examples include, the case of OilNow an app normally used to find gas stations, which started to include information on drive-through testing centers to its repertoire and various apps which showed the availability of masks in real time. (Lee and Lee 2020)

Due to the extrordinary amount of tracing data revealed through the government, which can only be compared to Israel, and these apps, a more traditional contact tracing app, that records interactions as in Chile India or Germany was not necessary. The Netherlands wanted to take a similar approach, but stopped due to privacy concerns.

After traditional measures did not suffice to meet the demand for masks, a supply stabilization measure was put in place on March 9. The government secured 80% of the country’s supply of around 10 million a day, to distribute 2 million of them directly to medical facilities and supplied the rest through pharmacies and other public sales channels with a 5 day rotation system and a 2 masks per person per week allowance (later raised to three). The mentioned digital system was put into place to avoid queuing. (Jeong et al. 2020) On June 12, the mask rationing system ended, after supply had been stabilized. (Yonhap 2020c)

The large testing capabilities of South Korea were made possible through collaborative actions between the government, academia and the private sector, based on emergency planning. (CGTN 2020) There have been no issues with the amounts of test kits available as South Korean Companies were able to begin exporting test kits as early as mid-February. (Kim, Kim, and Che 2020; Seegene 2020)

Along with the "social distancing in daily life" places with a significant risk of infection such as fitness centers and clubs will have to introduce QR-Codes at their entrances after June 30, that then have to be scanned by visitors, to help potential tracing efforts. (Cho 2020)

The most prolific examples of this are apps like Corona 100m which alerts the user if he or she comes into proximity of the path of confirmed patients or services like coronamap (link) which show the places confirmed patients visited on a map. Other examples include, the case of OilNow an app normally used to find gas stations, which started to include information on drive-through testing centers to its repertoire and various apps which showed the availability of masks in real time. (Lee and Lee 2020)

Due to the extrordinary amount of tracing data revealed through the government, which can only be compared to Israel, and these apps, a more traditional contact tracing app, that records interactions as in Chile India or Germany was not necessary. The Netherlands wanted to take a similar approach, but stopped due to privacy concerns.

After traditional measures did not suffice to meet the demand for masks, a supply stabilization measure was put in place on March 9. The government secured 80% of the country’s supply of around 10 million a day, to distribute 2 million of them directly to medical facilities and supplied the rest through pharmacies and other public sales channels with a 5 day rotation system and a 2 masks per person per week allowance (later raised to three). The mentioned digital system was put into place to avoid queuing. (Jeong et al. 2020) On June 12, the mask rationing system ended, after supply had been stabilized. (Yonhap 2020c)

The large testing capabilities of South Korea were made possible through collaborative actions between the government, academia and the private sector, based on emergency planning. (CGTN 2020) There have been no issues with the amounts of test kits available as South Korean Companies were able to begin exporting test kits as early as mid-February. (Kim, Kim, and Che 2020; Seegene 2020)

Along with the "social distancing in daily life" places with a significant risk of infection such as fitness centers and clubs will have to introduce QR-Codes at their entrances after June 30, that then have to be scanned by visitors, to help potential tracing efforts. (Cho 2020)

3.6 Social Distancing

Daycare centers for children have remained closed since February 27 as well as 15 types of social welfare facilities for vulnerable groups such as seniors and the disabled since February 28, though critical services such as meals for children have been available continuously. (CDSCH 2020)

The first social distancing measures were announced on February 29 and lasted until March 21 including recommendations to refrain from leaving their home, taking part in mass gatherings or meeting with multiple people in an enclosed space.

Reinforced social distancing lasted from March 22 to May 5, initially planned for 15 days and later extended by two Weeks on April 6 included recommendations for public to stay home and ordering closure of religious facilities, indoor gyms, entertainment facilities and private educational institutes. Companies were advised to make working from home possible and where not possible had to follow guidelines to prevent infection. Partial relaxations for low risk facilities operating outdoors or with enough space like museums were permitted after April 6. (MoFA 2020)

The measures were eased to social distancing in daily life on May 6, which tries to combine economic and social activities with infection prevention and control. This decision was prepared by an inter-ministerial task-force and an “everyday life quarantine” ad-hoc committee composed of medical experts, economists, representatives of civil society and government officials from mid-April onwards, because of the then stabilizing trend of infections, and an increasing dissatisfaction in the South Korean population.

Results were two major guidelines one for personal safety and one for communities, the latter of which contains 31 sub-guidelines tackling everything from workplaces over public baths to zoos.

The governments message has been, that this is not a move “back to normal” but long term shifts necessary to stay safe. Pretty much all of these measures have been recommendations only, as people have reacted very well to them and adjusted their daily lives enough to flatten the curve. (Kim, Kung and Abdelmalek 2020; MoFA 2020)

The first social distancing measures were announced on February 29 and lasted until March 21 including recommendations to refrain from leaving their home, taking part in mass gatherings or meeting with multiple people in an enclosed space.

Reinforced social distancing lasted from March 22 to May 5, initially planned for 15 days and later extended by two Weeks on April 6 included recommendations for public to stay home and ordering closure of religious facilities, indoor gyms, entertainment facilities and private educational institutes. Companies were advised to make working from home possible and where not possible had to follow guidelines to prevent infection. Partial relaxations for low risk facilities operating outdoors or with enough space like museums were permitted after April 6. (MoFA 2020)

The measures were eased to social distancing in daily life on May 6, which tries to combine economic and social activities with infection prevention and control. This decision was prepared by an inter-ministerial task-force and an “everyday life quarantine” ad-hoc committee composed of medical experts, economists, representatives of civil society and government officials from mid-April onwards, because of the then stabilizing trend of infections, and an increasing dissatisfaction in the South Korean population.

Results were two major guidelines one for personal safety and one for communities, the latter of which contains 31 sub-guidelines tackling everything from workplaces over public baths to zoos.

The governments message has been, that this is not a move “back to normal” but long term shifts necessary to stay safe. Pretty much all of these measures have been recommendations only, as people have reacted very well to them and adjusted their daily lives enough to flatten the curve. (Kim, Kung and Abdelmalek 2020; MoFA 2020)

3.7 Economic Policy

The South Korean governement set up a variety of programs to aid companies and the people in these economically challenging times.

These include support programs for owners of shops that had to close after being visited by confirmed patients, supporting rental fees and employment costs for various types of businesses, as well as granting tax breaks and suspending tax investigations. Further the government supports regions and local authorities financially in their efforts to help businesses and invests in the modernization of tourist attractions as well as reducing rates for loans. Finally workers/consumers benefit from consumption coupons, support for living expenses if they belong to a vulnerable group or are self quarantined, as well as a tax relief. These measures are mostly financed by the extra budgets discussed above. (Korean Government 2020)

These include support programs for owners of shops that had to close after being visited by confirmed patients, supporting rental fees and employment costs for various types of businesses, as well as granting tax breaks and suspending tax investigations. Further the government supports regions and local authorities financially in their efforts to help businesses and invests in the modernization of tourist attractions as well as reducing rates for loans. Finally workers/consumers benefit from consumption coupons, support for living expenses if they belong to a vulnerable group or are self quarantined, as well as a tax relief. These measures are mostly financed by the extra budgets discussed above. (Korean Government 2020)

3.8 Borders and Foreigners

Dealing with imported cases has been very important for South Korea, in the beginning due to the close geographical and economical proximity to China, later also because of travelers from Europe and the US that consistently made up around 10% of cases. South Korea avoided banning entry for large parts of the world, opposite to what many other countries did.

- Phase I: Only travelers from select affected countries were subject to Special Entry Procedures and the Self-health check mobile app to monitor their health for 14 days after arrival. After Covid-19 was declared a global pandemic all travelers from abroad became subject to these measures on March 19.

- Phase II: Mandatory testing for inbound travelers from Europe (March 22) and the US (April 15), negative testers were still required to self-quarantine.

- Phase III: Mandatory 14-day quarantine for all inbound travelers from April 1, either at home, or in government facilities. Waivers could be obtained from the embassy/consulate prior to entry.

- Phase IV: Suspension of the waiver program for countries with entry bans for travelers from South Korea on April 13. All inbound travelers are required to download the self-quarantine app.

- Phase V: Mandatory testing for all inbound travelers, if tested negative they still have to self-quarantine for 14 days.

3.9 Holding National Elections

On April 15 South Korea held national elections for the national assembly, as scheduled. Prior, there were concerns about turnout and proper campaigning as well as a potential spread of the virus.

The total turnout reached 66.2% (more than 29 million voters), the highest in 28 years, and as of May 10 no new cases were attributed to the election.

South Korea offers three relevant voting methods (there are five in total including overseas and shipboard voting): In person voting on election day, which is a national holiday, absentee voting, which is early in person voting and voting by mail, which is only offered to persons unable to vote in person due to disabilities, hospitalization or detention.

Several measures were put in place to manage the risk of holding a national election during the pandemic. For all forms of in person voting voters were required to wear masks and single use gloves, maintain social distancing, and checked for fevers. Those with fevers, followed a slightly different voting process in a separate space with more ventilation, where the utensils and the booth were disinfected after each voter and the tasks of signing the voter registration lists and submitting the ballot where carried out by officials in protective gear under observation.

Persons under self-quarantine followed a similar procedure as the ones with fevers, only after the normal voting time had ended, with the requirement to report their movements to their assigned government officials.

Covid-19 patients were allowed to use voting by mail, after pre-registration. Those who tested positive after the registration period were placed in eight designated treatment centers, where they could vote during the absentee voting period. (MoFA 2020)

Opposite to the positve outcome and reaction to the elections in South Korea, the holding of elections in France and Croatia was criticised strongly and also blamed for some additional cases.

The total turnout reached 66.2% (more than 29 million voters), the highest in 28 years, and as of May 10 no new cases were attributed to the election.

South Korea offers three relevant voting methods (there are five in total including overseas and shipboard voting): In person voting on election day, which is a national holiday, absentee voting, which is early in person voting and voting by mail, which is only offered to persons unable to vote in person due to disabilities, hospitalization or detention.

Several measures were put in place to manage the risk of holding a national election during the pandemic. For all forms of in person voting voters were required to wear masks and single use gloves, maintain social distancing, and checked for fevers. Those with fevers, followed a slightly different voting process in a separate space with more ventilation, where the utensils and the booth were disinfected after each voter and the tasks of signing the voter registration lists and submitting the ballot where carried out by officials in protective gear under observation.

Persons under self-quarantine followed a similar procedure as the ones with fevers, only after the normal voting time had ended, with the requirement to report their movements to their assigned government officials.

Covid-19 patients were allowed to use voting by mail, after pre-registration. Those who tested positive after the registration period were placed in eight designated treatment centers, where they could vote during the absentee voting period. (MoFA 2020)

Opposite to the positve outcome and reaction to the elections in South Korea, the holding of elections in France and Croatia was criticised strongly and also blamed for some additional cases.

3.10 Schools

Schools were initially not closed in a coordinated fashion, some decided not to reopen after the winter holidays at the end of January, others were ordered to stay closed in some smaller provinces. (Yonhap 2020a) From February 23 onwards all schools stayed closed because the start of the academic year was postponed by the Ministry of Education, initially for a week which was later extended to April 6. Then schools gradually restarted with online education. On May 6 together with the ease of social distancing measures, the gradual reopening of schools was announced, which then happened from May 13 to June 8. (MoFA 2020)

It is important to note that many South Korean children go to private cram schools called “hagwon” in the afternoon and evening, these often only closed when they had to during the more intense social distancing measures from March 22 to May 5. (Park 2020)

It is important to note that many South Korean children go to private cram schools called “hagwon” in the afternoon and evening, these often only closed when they had to during the more intense social distancing measures from March 22 to May 5. (Park 2020)

4 Meaning Making, Crisis Communication and Legitimacy

Meaning making is described by Boin et al. (2017) as the process which creates a dominant understanding of a crisis in the society. In this process public leaders, usually politicians, play a special role due to their unique position of being expected to guide in times of crisis, against other actors trying to bring their own frames into the discussion. These other actors include the Media as well as the citizenry. Boin et al. suggest crucial factors in this process, which decide over success or failure of the leaders to determine the narrative used in the crisis.

The first factor is a successful initial framing of the situation. This first frame generally sets the boundaries of discussion and action for the duration of the crisis, but it is also the standard the leaders will be compared to.

This process usually begins with the definition of the situation as a crisis itself.

In South Korea the Covid-19 Pandemic was framed by the government as a serious crisis from the very start, a view which was not challenged in society at large, commentators often explain this with the MERS outbreak from 2015 and previous ones of other infectious diseases still being fresh in the minds of the Koreans. (Dudden and Marks 2020)

Interestingly in Sweden a previous outbreak, in this case of H1N1, had the opposite effect as the response then was seen as an overreaction, which can be seen as one source for the more laissez-faire approach taken in the current Pandemic.

On January 30th, just 10 days after the first reported case, President Moon Jae-in held a meeting with his cabinet, the provincial governors and important mayors via video conferencing to coordinate the efforts against the novel coronavirus, in his opening speech the outbreak is established as a serious crisis, which forces immediate and drastic action by the government and the people. (Moon 2020b)

"There can be no compromise when it comes to protecting public safety. Preparations should be made for all possible circumstances, and all necessary steps should be taken. The earlier preemptive preventive measures are employed, the more effective they are. These measures should be strong enough to the point of being considered excessive."

According to Boin et al. with the initial frame, has to come a persuasive narrative, consisting of a credible explanation, guidance and a call to action while facilitating hope at the same time, in part by suggesting that leaders are in control. Pretty much all of these aspects can be found in Moons speech from that day.

“We have the world’s best infectious disease prevention and control capabilities. We also have accumulated experience from past incidents. Moreover, the Government is doing its best. We will be able to prevail successfully provided that the people and local communities cooperate. If the central and local governments go to any length together to do their work and each and every one of us thoroughly sticks to the guidelines for preventing the spread of disease, we will be able to surmount this while minimizing damage from the new coronavirus.“

The credible explanation part being supplied by the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters in the morning and by the Central Disease Control Headquarters in the afternoon, additionally to the broad information made available every day on the Website of KCDC.

Further the local governments use their ability to send emergency SMS messages daily, to inform the people in their boundaries about newly confirmed patients, their trajectories, and policies. These messages arrive with loud alarms and often contain only basic information which has raised the concern of over-alerting. (Lee and Lee 2020)

The reputation of Moon Jae-in and his government was far from perfect when the crisis began. He came into power in an irregular election in 2017 after the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye due to corruption, with a landslide victory and high approval ratings, which receded massively in late 2019 due to economic problems and a scandal involving one of his ministers, to a barely positive rating. (Lee 2019; Ray 2020)

So personal and in part organizational credibility as it is called by Boin et al. was not the highest when the crisis hit, but this frame was still widely accepted because of the exemplary communication by the government and MERS, that left a spook in South Korean society, so that the frame was already there and it only had to be fitted to the crisis at hand.

This kind of effective crisis communication was not pursued in all countries of this Wiki, negative examples include Brazil, France, and Iran while Taiwan may be a positive example.

This consensus about the definition of Covid-19 as a crisis did not necessarily carry over into the discussion how to handle it and especially who, if anyone, is to blame, as some of the usual cleavages and antagonisms of South Korean society have been reinforced by the Covid-19 crisis.

Shincheonji is a religious, quasi-Christian group with around 250.000 members that came to larger public attention when the so called “Patient 31” attended two services of the church in Daegu, a city of 2.5 million, whilst already showing symptoms and set off a chain of infections, that accounted for more than half of South Koreas cases in the beginning of the outbreak. (Rashid 2020) She was tested positive for the virus on February 18 as were many of her contacts in the following days, while being hospitalized for unrelated reasons the days before, some South Korean media claimed she rejected being tested twice, which she denies. (Introvigne et al. 2020) The churches practices of large gatherings in close proximity with much singing and vocal praying that often last between two and three hours most likely enhanced the spread of the virus greatly. (Wong 2020)

A general climate of distrust against Shincheonji has already been established in South Korea before the Covid-19 crisis (for reasons see: (Introvigne et al. 2020), after the incident above the actors responsible for that pushed the narrative that Shincheonji did not cooperate with the government regarding lists of its members based on the fact that many members of Shincheonji hide their affiliation in public, which is most likely due to the severe repercussions they face when their beliefs become public. In fact, Shincheonji cooperated well with the authorities, closing their services in Daegu the same day “Patient 31” was confirmed. Headlines about non-cooperation were manufactured from misunderstandings, for example when Shincheonji only gave a list of national members, which was obviously lower than the official numbers on their website which included international members. (Introvigne et al. 2020)

Hostilities and accusations against the church were so high, that the police ended up raiding their offices, finding the lists to be largely correct. Further petitions to dismantle the church were launched and gained over a million signatures. Finally the mayor of Seoul filed a criminal complaint against the leaders of the church for murder and violations of government measures. (Kim 2020; Sangmi 2020; Shim 2020) France also reported a significant cluster linked to a religious gathering.

Also, the common Anti-Chinese sentiment has been very relevant with the virus originating in China. After case numbers exploded in late February after the Shincheonji superspreader event, many demanded a ban on Chinese nationals coming to the country, even though rigorous and successful testing and quarantine of any foreigners and nationals coming into the country was already in place. Further, but to a lesser degree, the governments crisis management was criticized when prices for masks were high, but Moon publicly donated some 3 million to China and hand sanitizer was hard to find during the initial weeks of the pandemic. The Korean Medical Association (KMA) demanded a more active response from the government, calling for the control of mask prices, more support for medical institutions and blocking entrance from China.

Over the course of February a petition to impeach President Moon over his crisis management especially towards China gained more than a million signatures, which is a high number for the governments petition tool though another petition supporting Moon gained its own million signatures in just a couple of days. (Kang 2020)

In the response to these petitions the government defended its stance toward China by citing low numbers of infections connected to Chinese nationals and its rigorous system for incoming travelers. (Moon 2020a)

I was unable to find good data on trust in public institutions in general, especially timeseries data. President Moons approval rating has seen a massive rise during the pandemic after the initial reservations discussed above. The decline in May and June is largely credited to tensions with North Korea. (Korea Gallup Research Institute 2020) The Ministry of Health and Welfare has also seen a big rise in its performance evaluation, which was already comparatively high before the crisis began. (realmeter 2020) Finally, the results of the national election show strong support for the government as the governing Democratic party won a 3/5 supermajority, the largest in South Korean democratic history since 1987, in the national assembly which grants it special legislative rights. (Jung 2020)

Many of the topics which were heavily contested in many western countries revolving around the measures taken and specifically them being an overreaction of some sort were not an issue in South Korea. A common argument, especially in the West, to explain the success of Asian countries in stopping the spread of Covid-19 has been some kind of Confucian culture of obedience, this is far from the truth as the many petitions and demands mentioned above clearly show, after all it was the continuous protest of millions of Koreans, that lead to the impeachment of Park Geun-hye that brought Moon into office.

A variety of other reasons has been discussed, that jointly might be able to explain the differences.

The issue of transparency has been central in the South Korean crisis discussion.

Transparency is used differently from the usual meaning often assumed in western countries, where it refers to an openness about the governments processes there, it refers to a demand of detailed information about the spread of the virus in the South Korean case, which may again by due to the MERS outbreak in 2015, where the public perceived a lack of information. This sentiment was promptly addressed by President Moon in a speech early on in the crisis, where he urged the responsible agencies “to disclose all necessary information in the most transparent, swift and detailed manner in order to meet public expectations so that people will not withdraw from their daily lives and unnecessary misunderstandings and speculations will not arise.” (Moon 2020b) This view has likely played a major role in legitimizing the vast amount of personal information disclosed about Covid-19 Patients.

The first factor is a successful initial framing of the situation. This first frame generally sets the boundaries of discussion and action for the duration of the crisis, but it is also the standard the leaders will be compared to.

This process usually begins with the definition of the situation as a crisis itself.

In South Korea the Covid-19 Pandemic was framed by the government as a serious crisis from the very start, a view which was not challenged in society at large, commentators often explain this with the MERS outbreak from 2015 and previous ones of other infectious diseases still being fresh in the minds of the Koreans. (Dudden and Marks 2020)

Interestingly in Sweden a previous outbreak, in this case of H1N1, had the opposite effect as the response then was seen as an overreaction, which can be seen as one source for the more laissez-faire approach taken in the current Pandemic.

On January 30th, just 10 days after the first reported case, President Moon Jae-in held a meeting with his cabinet, the provincial governors and important mayors via video conferencing to coordinate the efforts against the novel coronavirus, in his opening speech the outbreak is established as a serious crisis, which forces immediate and drastic action by the government and the people. (Moon 2020b)

"There can be no compromise when it comes to protecting public safety. Preparations should be made for all possible circumstances, and all necessary steps should be taken. The earlier preemptive preventive measures are employed, the more effective they are. These measures should be strong enough to the point of being considered excessive."

According to Boin et al. with the initial frame, has to come a persuasive narrative, consisting of a credible explanation, guidance and a call to action while facilitating hope at the same time, in part by suggesting that leaders are in control. Pretty much all of these aspects can be found in Moons speech from that day.

“We have the world’s best infectious disease prevention and control capabilities. We also have accumulated experience from past incidents. Moreover, the Government is doing its best. We will be able to prevail successfully provided that the people and local communities cooperate. If the central and local governments go to any length together to do their work and each and every one of us thoroughly sticks to the guidelines for preventing the spread of disease, we will be able to surmount this while minimizing damage from the new coronavirus.“

The credible explanation part being supplied by the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters in the morning and by the Central Disease Control Headquarters in the afternoon, additionally to the broad information made available every day on the Website of KCDC.

Further the local governments use their ability to send emergency SMS messages daily, to inform the people in their boundaries about newly confirmed patients, their trajectories, and policies. These messages arrive with loud alarms and often contain only basic information which has raised the concern of over-alerting. (Lee and Lee 2020)

The reputation of Moon Jae-in and his government was far from perfect when the crisis began. He came into power in an irregular election in 2017 after the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye due to corruption, with a landslide victory and high approval ratings, which receded massively in late 2019 due to economic problems and a scandal involving one of his ministers, to a barely positive rating. (Lee 2019; Ray 2020)

So personal and in part organizational credibility as it is called by Boin et al. was not the highest when the crisis hit, but this frame was still widely accepted because of the exemplary communication by the government and MERS, that left a spook in South Korean society, so that the frame was already there and it only had to be fitted to the crisis at hand.

This kind of effective crisis communication was not pursued in all countries of this Wiki, negative examples include Brazil, France, and Iran while Taiwan may be a positive example.

This consensus about the definition of Covid-19 as a crisis did not necessarily carry over into the discussion how to handle it and especially who, if anyone, is to blame, as some of the usual cleavages and antagonisms of South Korean society have been reinforced by the Covid-19 crisis.

Shincheonji is a religious, quasi-Christian group with around 250.000 members that came to larger public attention when the so called “Patient 31” attended two services of the church in Daegu, a city of 2.5 million, whilst already showing symptoms and set off a chain of infections, that accounted for more than half of South Koreas cases in the beginning of the outbreak. (Rashid 2020) She was tested positive for the virus on February 18 as were many of her contacts in the following days, while being hospitalized for unrelated reasons the days before, some South Korean media claimed she rejected being tested twice, which she denies. (Introvigne et al. 2020) The churches practices of large gatherings in close proximity with much singing and vocal praying that often last between two and three hours most likely enhanced the spread of the virus greatly. (Wong 2020)

A general climate of distrust against Shincheonji has already been established in South Korea before the Covid-19 crisis (for reasons see: (Introvigne et al. 2020), after the incident above the actors responsible for that pushed the narrative that Shincheonji did not cooperate with the government regarding lists of its members based on the fact that many members of Shincheonji hide their affiliation in public, which is most likely due to the severe repercussions they face when their beliefs become public. In fact, Shincheonji cooperated well with the authorities, closing their services in Daegu the same day “Patient 31” was confirmed. Headlines about non-cooperation were manufactured from misunderstandings, for example when Shincheonji only gave a list of national members, which was obviously lower than the official numbers on their website which included international members. (Introvigne et al. 2020)

Hostilities and accusations against the church were so high, that the police ended up raiding their offices, finding the lists to be largely correct. Further petitions to dismantle the church were launched and gained over a million signatures. Finally the mayor of Seoul filed a criminal complaint against the leaders of the church for murder and violations of government measures. (Kim 2020; Sangmi 2020; Shim 2020) France also reported a significant cluster linked to a religious gathering.

Also, the common Anti-Chinese sentiment has been very relevant with the virus originating in China. After case numbers exploded in late February after the Shincheonji superspreader event, many demanded a ban on Chinese nationals coming to the country, even though rigorous and successful testing and quarantine of any foreigners and nationals coming into the country was already in place. Further, but to a lesser degree, the governments crisis management was criticized when prices for masks were high, but Moon publicly donated some 3 million to China and hand sanitizer was hard to find during the initial weeks of the pandemic. The Korean Medical Association (KMA) demanded a more active response from the government, calling for the control of mask prices, more support for medical institutions and blocking entrance from China.

Over the course of February a petition to impeach President Moon over his crisis management especially towards China gained more than a million signatures, which is a high number for the governments petition tool though another petition supporting Moon gained its own million signatures in just a couple of days. (Kang 2020)

In the response to these petitions the government defended its stance toward China by citing low numbers of infections connected to Chinese nationals and its rigorous system for incoming travelers. (Moon 2020a)

I was unable to find good data on trust in public institutions in general, especially timeseries data. President Moons approval rating has seen a massive rise during the pandemic after the initial reservations discussed above. The decline in May and June is largely credited to tensions with North Korea. (Korea Gallup Research Institute 2020) The Ministry of Health and Welfare has also seen a big rise in its performance evaluation, which was already comparatively high before the crisis began. (realmeter 2020) Finally, the results of the national election show strong support for the government as the governing Democratic party won a 3/5 supermajority, the largest in South Korean democratic history since 1987, in the national assembly which grants it special legislative rights. (Jung 2020)

Many of the topics which were heavily contested in many western countries revolving around the measures taken and specifically them being an overreaction of some sort were not an issue in South Korea. A common argument, especially in the West, to explain the success of Asian countries in stopping the spread of Covid-19 has been some kind of Confucian culture of obedience, this is far from the truth as the many petitions and demands mentioned above clearly show, after all it was the continuous protest of millions of Koreans, that lead to the impeachment of Park Geun-hye that brought Moon into office.

A variety of other reasons has been discussed, that jointly might be able to explain the differences.

- The MERS outbreak in 2015 may not only have helped with the framing of the current crisis, but also prepared the people for the necessary measures (Breen 2020)

- South Koreans in general are more used to wearing face masks in public due to notoriously bad air quality and dust storms (Breen 2020; The Korea Times 2019; Thompson 2020)

- General trust in scientists was used by the government to convince people by trying to keep politics out of the recommendations for behavior. (Dudden and Marks 2020; Thompson 2020)

- The government has made an effort to quickly respond to fake news with a cooperation between the Korea Communications Commission, the National Police Agency and the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism among others. (CDSCH 2020)

- There has been strong societal pressure to conform to the measures put in place, fueled in part by other countries looking at South Korea as a positive example, which also quickly quieted many critics. (Mayberry and Pietromarchi 2020; Thompson 2020)

- Finally all of the factors above made it possible for the government to deal with Covid-19 without imposing all to restrictive rules on its citizens. (McCurry 2020)

The issue of transparency has been central in the South Korean crisis discussion.

Transparency is used differently from the usual meaning often assumed in western countries, where it refers to an openness about the governments processes there, it refers to a demand of detailed information about the spread of the virus in the South Korean case, which may again by due to the MERS outbreak in 2015, where the public perceived a lack of information. This sentiment was promptly addressed by President Moon in a speech early on in the crisis, where he urged the responsible agencies “to disclose all necessary information in the most transparent, swift and detailed manner in order to meet public expectations so that people will not withdraw from their daily lives and unnecessary misunderstandings and speculations will not arise.” (Moon 2020b) This view has likely played a major role in legitimizing the vast amount of personal information disclosed about Covid-19 Patients.

5 Comparison

In this paragraph I want to compare the South Korean response to some other cases in the Wiki.

The two most interesting cases of comparison due to a variety of similarities are the Netherlands and Taiwan.

Taiwan is probably the most similar country to South Korea, as both are in very close proximity to China and took early action against the virus, with similar measures, such as strong digital tracing, a very similar mask rationing scheme all while avoiding lockdowns (for some more see my comment on the Taiwan wiki) The difference in case numbers is therefore even more striking as Taiwan experienced only 3% of cases with a population a little less than half the size, reasons for this can only be speculated so far, though they may include less time to prepare as the main outbreak in South Korea happened earlier, and that this initial outbreak was of much larger scale which then may have lead to more community transmission which is difficult to fully contain.

The Netherlands are also an interesting case for comparison as it tried to combat the crisis in a very similar manner, based on excessive digital contact tracing and recommendations for adjusted behavior without lockdowns, though somewhat failed to do so because of privacy concerns and ended up with almost four times as many cases as South Korea (which may also be due to the relative proximity to many western European hotspots).