India

Seitenübersicht

[Ausblenden]1 Preparedness

Preparedness refers to how well a state is prepared to prevent and to minimise the effects of a crisis. In this section I will give an overview of various disaster management plans/guidelines in India and take a closer look at the Indian health system. Subsequently, I will evaluate the preparedness of India for the coronavirus and compare it to other countries using the GHS Index.

1.1 National Disaster Management Plan

The government of India published a National Disaster Management Plan (NDMP) in November 2019. The plan serves as a general framework to understand the nature and risks of possible disasters and to strengthen the capacity for disaster management.

Epidemics are categorized as biological natural hazards. The Ministry for Health and Family Welfare (MHFW) is the central agency designated to deal with epidemics and is responsible for the coordination and operation of epidemiological surveillance. Disease containment through social distancing measures, isolation, and restrictions of movement is put forward as a main strategy, especially in the early stages of an epidemic. Overall, the plan is based strongly on international agreements and epidemics are recognized as global threats.

To take a look at the full NDMP click here

Epidemics are categorized as biological natural hazards. The Ministry for Health and Family Welfare (MHFW) is the central agency designated to deal with epidemics and is responsible for the coordination and operation of epidemiological surveillance. Disease containment through social distancing measures, isolation, and restrictions of movement is put forward as a main strategy, especially in the early stages of an epidemic. Overall, the plan is based strongly on international agreements and epidemics are recognized as global threats.

To take a look at the full NDMP click here

1.2 National Disaster Management Guidelines

The National Disaster Management Guideline (NDMG) for the management of biological disasters was developed by the Indian Government in 2008. It provides a legal framework and actual guidelines for the development of a response plan in case of an epidemic. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) is the responsible agency for an effective disaster management, through the coordination of policies and the ensuring of preparedness of all involved actors.

Section 4 specifies guidelines for biological disaster management, which is based on recommendations from the International Health Regulations (IHR). The two main areas of focus are Prevention and Preparedness.

Prevention:

To take a look at the full NDMG click here.

Section 4 specifies guidelines for biological disaster management, which is based on recommendations from the International Health Regulations (IHR). The two main areas of focus are Prevention and Preparedness.

Prevention:

- Risk assessment and vulnerability analysis

- Environmental management, which includes water supply, personal hygiene, vector control, burial of the dead

- Establishment of a disease surveillance system with a four step detection and containment: (1) Recognition and diagnosis (2) Communication of surveillance information to public health authorities (3) Epidemiological analysis (4) delivery of appropriate medical treatment and public health measures

- Capacity Development: construction of a well functioning organisation and a centralized system for data collection across levels

- Training for specialists

- Community Preparedness: sensitise local health practitioners on the threat and impact of disaster and start media awareness campaigns

- Strengthen a network of laboratories

To take a look at the full NDMG click here.

1.3 The Epidemic Disease Act

The Epidemic Disease Act was developed in colonial India to tackle the bubonic plague that broke out in Mumbai in the 1890s and was passed in 1897 with the aim to increase the capacities to prevent the outbreak of diseases (Ps, 2016). It defines the powers of the state and the central government in case of an epidemic.

Powers of the state

“When the state government is satisfied that the state or any part thereof is visited by or threatened with an outbreak of any dangerous epidemic disease, the state government if it thinks that the ordinary provisions of the law are insufficient for the purpose, may take, or require or empower any person to take such measures and, by public notice, prescribe such temporary regulations to be observed by the public (…) The state government may take measures and prescribe regulations for inspection of persons travelling by railway or otherwise, and the segregation, in hospital, temporary accommodation or otherwise, of persons suspected by the inspecting officer of being infected with any such disease.” (The Epidemics Disease Act of 1897, §2, p.2)

Powers of the Central Government

“When the Central Government is satisfied that India or any part thereof is visited by, or threatened with, an outbreak of any dangerous epidemic disease and that the ordinary provisions of the law for the time being in force are insufficient to prevent the outbreak of such disease or the spread thereof, the Central Government may take measures and prescribe regulations for the inspection of any ship or vessel leaving or arriving at any port in and for such detention thereof, or of any person intending to sail therein, or arriving thereby, as may be necessary” (The Epidemics Disease Act of 1897, §2A, p.3)

Furthermore, the act defines penalties for a anyone who disobeys the regulations.

To take a look at the full document click here

Powers of the state

“When the state government is satisfied that the state or any part thereof is visited by or threatened with an outbreak of any dangerous epidemic disease, the state government if it thinks that the ordinary provisions of the law are insufficient for the purpose, may take, or require or empower any person to take such measures and, by public notice, prescribe such temporary regulations to be observed by the public (…) The state government may take measures and prescribe regulations for inspection of persons travelling by railway or otherwise, and the segregation, in hospital, temporary accommodation or otherwise, of persons suspected by the inspecting officer of being infected with any such disease.” (The Epidemics Disease Act of 1897, §2, p.2)

Powers of the Central Government

“When the Central Government is satisfied that India or any part thereof is visited by, or threatened with, an outbreak of any dangerous epidemic disease and that the ordinary provisions of the law for the time being in force are insufficient to prevent the outbreak of such disease or the spread thereof, the Central Government may take measures and prescribe regulations for the inspection of any ship or vessel leaving or arriving at any port in and for such detention thereof, or of any person intending to sail therein, or arriving thereby, as may be necessary” (The Epidemics Disease Act of 1897, §2A, p.3)

Furthermore, the act defines penalties for a anyone who disobeys the regulations.

To take a look at the full document click here

1.4 Health System

Like the Consitution of Iran, the Indian constitution guarantees a right to health and obliges the states to provide free universal health care for every citizen [1] . The health-care system in India includes a combination of public and private service providers (Chokshi et al., 2016). Sheikh, Saligram & Hort (2015) refer to a “mixed health system syndrome”, which lacks quality and equity. “The adverse impacts of this syndrome for users of care are severe, and include high, frequently catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures on health care contributing to impoverishment of households; poor quality of care affecting the health of individuals as well as communities; frequent discrimination, denial of care and exploitation and outright unavailability of health care from qualified providers in villages as a result of their preferences for urban areas” (Sheik et al., 2015, p. 40). The National rural health mission (NRHM) was launched in 2005 to improve health care in rural areas and several governmental programmes were launched to help poor households afford care, however, the success of the initiatives seems rather limited. The out-of-pocket health expenditures have for example not significantly decreased since 2000 [2]

The underfunding of the health system is an urgent issue. The Spending for Health Expenditure in India accounts for 3.6% of the GDP compared to a worldwide average of 9.8% or in the Netherlands 10.1% [3] . In India there are 0.7 hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants compared to 8.3 in Germany for example [4] . People who are diagnosed with Corona Virus may show symptoms like severe chest pain and difficulty breathing, and hence, are in need of a critical care bed equipped with a ventilator. In India there are 2.3 critical care beds per 100,000 inhabitants (Phua et al., 2020) compared to 29.2 in Germany (Rhodes et al., 2012). The distribution of health care workers across India is very uneven, as they mostly concentrate in urban areas. The total number of health care workers is also significantly lower in comparison to other countries . There are 0.7 physicians and 1.5 nurses/midwives per 1000 inhabitants in India compared to 4.1 physicians and 12.9 nurses/midwifes in Germany [5] [6] .

The underfunding of the health system is an urgent issue. The Spending for Health Expenditure in India accounts for 3.6% of the GDP compared to a worldwide average of 9.8% or in the Netherlands 10.1% [3] . In India there are 0.7 hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants compared to 8.3 in Germany for example [4] . People who are diagnosed with Corona Virus may show symptoms like severe chest pain and difficulty breathing, and hence, are in need of a critical care bed equipped with a ventilator. In India there are 2.3 critical care beds per 100,000 inhabitants (Phua et al., 2020) compared to 29.2 in Germany (Rhodes et al., 2012). The distribution of health care workers across India is very uneven, as they mostly concentrate in urban areas. The total number of health care workers is also significantly lower in comparison to other countries . There are 0.7 physicians and 1.5 nurses/midwives per 1000 inhabitants in India compared to 4.1 physicians and 12.9 nurses/midwifes in Germany [5] [6] .

1.5 GHS Index

The Global Health Security Index (GHS Index) provides an extensive assessment of a country’s healthy security and capability to manage the outbreak of infectious diseases. India’s overall score is 46.5 out of 100. India ranks 57th worldwide and 1st in Southern Asia. Iran for example has a significantly lower score of 37,7, whereas Bulgaria has a similar score of 45.6 [7]

The category “Detect” includes an assessment of the epidemiology workforce. India receives a score of 50/100, indicating that they meet half of the requirements put forward by the GHS Index. A strength of the epidemiology workforce in India is the applied epidemiology training programme for workers in public health agencies. However, the Country does not have 1 trained field epidemiologist per 200,000 people as recommended by the international Health Regulations (Williams et al., 2020).

In the category “Respond” the emergency preparedness and response planning is assessed. Although the NDMP and NDMG do exist, their implementation is rated rather low, resulting in a score of only 12.5. Another indicator is the frequent exercising of emergency situations. India received a full score in this category because they participated in biological threat-focused IHR exercises with the WHO in the past year.

The category “Detect” includes an assessment of the epidemiology workforce. India receives a score of 50/100, indicating that they meet half of the requirements put forward by the GHS Index. A strength of the epidemiology workforce in India is the applied epidemiology training programme for workers in public health agencies. However, the Country does not have 1 trained field epidemiologist per 200,000 people as recommended by the international Health Regulations (Williams et al., 2020).

In the category “Respond” the emergency preparedness and response planning is assessed. Although the NDMP and NDMG do exist, their implementation is rated rather low, resulting in a score of only 12.5. Another indicator is the frequent exercising of emergency situations. India received a full score in this category because they participated in biological threat-focused IHR exercises with the WHO in the past year.

1.6 Evaluation of Preparedness

A key factor of preparedness is that plans are updated regularly and adapted to changes in the environment and society. The Epidemic Disease Act has not been updated since 1897 and although it only provides a very general framework, could be adapted in order to be more time appropriate. The National Disaster Management Guidelines were last updated in 2008. Lessons learnt from the H1N1 pandemic in India in 2009 could for example not be taken into consideration. However, the overall framework for the management of crisis seems adequate, as it is strongly oriented on international regulations.

The lack of a special plan for vulnerable groups, such as migrant workers or people who live in slums, is highly problematic. Many people in urban India are crammed into small living spaces and overcrowding is generally an issue. Furthermore, vulnerable groups often do not have access to basic amenities, including clean water, sanitation and drainage (Kumar, 2015), making “corona-appropriate” behaviour nearly impossible. One can examine reinforcing cleavages in India during the epidemic, as existing inequalities and vulnerabilities are visibly exacerbating during the crisis.

Furthermore one must consider the strengths and weaknesses of formal planning during crisis management. Standard routines might be too specific and inappropriate to respond to a crisis. Extensive plans may give a false sense of preparedness and hinder re-evaluation of measures under new circumstances (Keller et al., 2012). On the other hand, the NDMP and NDMG can cause higher accountability, reliability and transparency of the public organisations and lead to an easier allocation of responsibility during the crisis (Keller et al., 2012).

The lack of a special plan for vulnerable groups, such as migrant workers or people who live in slums, is highly problematic. Many people in urban India are crammed into small living spaces and overcrowding is generally an issue. Furthermore, vulnerable groups often do not have access to basic amenities, including clean water, sanitation and drainage (Kumar, 2015), making “corona-appropriate” behaviour nearly impossible. One can examine reinforcing cleavages in India during the epidemic, as existing inequalities and vulnerabilities are visibly exacerbating during the crisis.

Furthermore one must consider the strengths and weaknesses of formal planning during crisis management. Standard routines might be too specific and inappropriate to respond to a crisis. Extensive plans may give a false sense of preparedness and hinder re-evaluation of measures under new circumstances (Keller et al., 2012). On the other hand, the NDMP and NDMG can cause higher accountability, reliability and transparency of the public organisations and lead to an easier allocation of responsibility during the crisis (Keller et al., 2012).

2 Sense-making

Sense making means "collecting and processing information that will help crisis managers to detect an emerging crisis and understand the significance of what is going on during a crisis" (Boin et al., 2017, p.15). In the following section the development of COVID-19 pandemic in India and how the country is testing and reporting on the crisis will be analyzed.

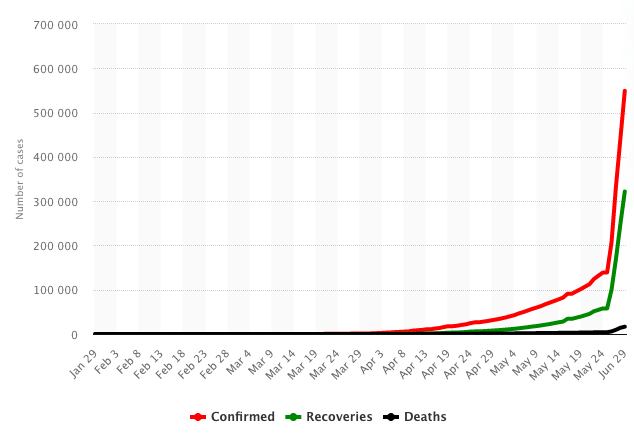

The first case of COVID-19 in India was reported on the 30th of January 2020. On July 14th, the country has confimed a total 878,254 cases [8] and 571459 recoveries [9] .

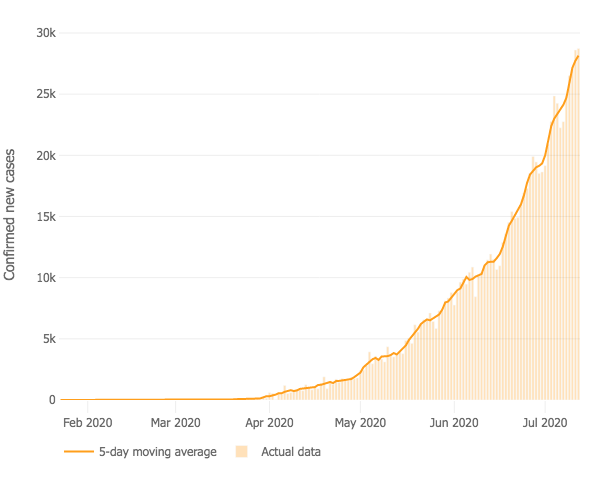

2.1 Development of Confirmed New Cases

The development of confirmed new cases shows whether a country has managed to "flatten the curve" and reduce the number of new COVID-19 cases over time. The graph shows that the number of confirmed new cases is on average constantly increasing in India, indicating that the measures taken to counter the outbreak of the pandemic are not far-reaching enough yet.

2.2 Mortality

India has confirmed a total of 23,174 deaths on July 14th and the observed case-fatality ratio, which is measured in deaths per 100 confirmed cases, is 2.8% [10] .

International Comparison of the observed case-fatality ratio (John Hopkins University)

The case-fatality ratio is influenced by many factors, such as the healthcare system and demographics. People who are 65 years old or older are for example considered part of the high-risk group [11] . The observed case-fatality ratio in France is significantly higher than in India. One possible explanation is that there are less high-risk patients in India, as only 6.18% of the population is older than 65 in India compared to 20.5% in France [12] . However, this demographical difference is most likely not a sufficient explanation for such discrepancies in the observed case-fatality ratio, especially considering that the overall health care in France is better than in India. An alternative explaination is the dissimilar test-capacity of the countries and a possibly high number of unconfirmed cases and unknown deaths.

2.3 Testing

In India approximately 1 test per 100,000 inhabitants is being conducted, which is significantly lower than the number of tests in other strongly affected countries, such as Brazil, wehere 32 tests and Chile, where 64 tests are being conducted per 100,000 inhabitants. [13] .

Due to the limited testing capacities, only the following people are being tested:

“All Symptomatic people who

Due to the limited testing capacities, only the following people are being tested:

“All Symptomatic people who

- Have history of international travel in last 14 days

- Had come in contact of confirmed cases

- Are healthcare workers

- Are hospitalized patients with Severe AcuteRespiratory Illness (SARI) or Influenza Like Illness (ILI) or severe pneumonia.

- Those living in the same household with a confirmed case

- Health workers who examined a confirmed case without adequate protection as per WHO recommendations” (Ministry of Health and an Welfare) [14]

2.4 Evaluation of Sense Making

The amount of tests that are being conducted in India is very low and thus the real scale of the pandemic is unknown. As the testing capacities in India were ramped up, the positivity rate of the tests also increased [17] , as depicted on the graph below. The positivity rate currently lies at 8.73%, which is above the recommended maximum of 5% positivity rate [18] . Internationally there is a large variance of positivity rates, South Korea has a low positivity rate of only about 1% and the positivity rate in Brazil is above 30%.

In general as the government increased the number of tests, the number of positive cases continually rose, which further confirms that not enough tests are being conducted in India. Furthermore, the testing logic is focused on limiting the spread of the virus, however, is not set up to discover new cases in previously unaffected communities.

3 Decision-making

Decision Making is defined as "making critical calls on strategic dillemas and orchestrating a coherent repsone to implement those decisions" (Boin et al., 2020, p.15). In the following section I will give a chronological overview of the decisions made by the government of India and highlight some key aspects. Furthermore, I will examine the coordination across different levels and take a closer look at the pro-active crisis management in the state of Kerala.

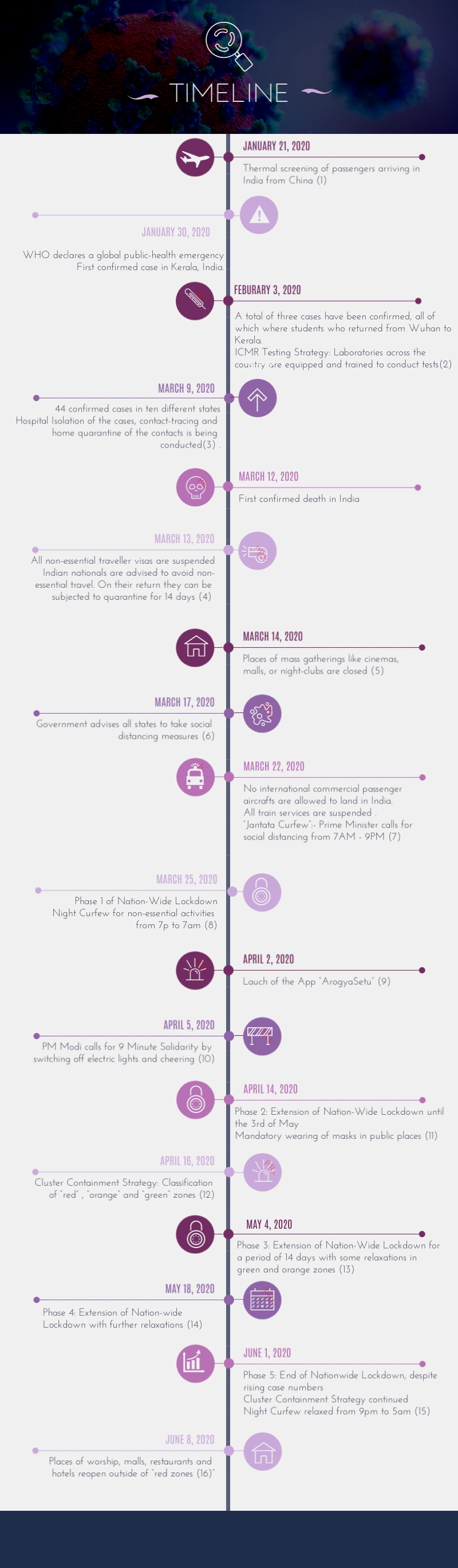

3.1 Timeline

3.2 Nation Wide Lockdown

In a special address to the nation on television, Prime Minister Modi announced a nation wide lockdown on the 25th of March 2020[19] . People were prohibited from stepping out of their home for non-essential activities. Provisions to ensure the supply of essential items were made. All transport services were suspended. All educational institutions were closed, but online and at home learning were allowed to continue. All places of mass gathering were closed, including malls, sport complexes, places or worship, auditoriums and many more.

Cluster Containment Strategy

“The Cluster Containment Strategy would be to contain the disease within a defined geographic area by early detection of cases, breaking the chain of transmission and thus preventing its spread to new areas. This would include geographic quarantine, social distancing measures, enhanced active surveillance, testing all suspected cases, isolation of cases, quarantine of contacts and risk communication to create awareness among public on preventive public health measures” (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Containmentplan for Lage Outbreaks, p.5) [20]

On April 16th the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Ministry of Home Affairs classified three zones[21] :

Green Zone: No confimed cases or no new cases in the last 21 days

Orange Zone: Neither Red nor Green zone

Red Zone: Highest case load districts contributing to more than 80% of cases for each state or in India and districts with a doubling rate below 4 days

Depending on the risk-assessment in the given region, relaxations may have been permitted starting from May 4th. [22]

To take a look at the Cluster Containment Strategy click here

Other countries have also followed a similar logic of classifying the country into three risk zones, for example Iran and France.

“The Cluster Containment Strategy would be to contain the disease within a defined geographic area by early detection of cases, breaking the chain of transmission and thus preventing its spread to new areas. This would include geographic quarantine, social distancing measures, enhanced active surveillance, testing all suspected cases, isolation of cases, quarantine of contacts and risk communication to create awareness among public on preventive public health measures” (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Containmentplan for Lage Outbreaks, p.5) [20]

On April 16th the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Ministry of Home Affairs classified three zones[21] :

Green Zone: No confimed cases or no new cases in the last 21 days

Orange Zone: Neither Red nor Green zone

Red Zone: Highest case load districts contributing to more than 80% of cases for each state or in India and districts with a doubling rate below 4 days

Depending on the risk-assessment in the given region, relaxations may have been permitted starting from May 4th. [22]

To take a look at the Cluster Containment Strategy click here

Other countries have also followed a similar logic of classifying the country into three risk zones, for example Iran and France.

3.3 "Unlocking Phase"

The WHO suggests that social distancing measures should only be lowered if the positivity rate is below 5% [23] . However, the Indian government ended the nation-wide lockdown on June 1st, while the number of new confirmed case was still rising and the positivity rate was above 5% [24] . The reason behind the seemily early end of the nationwide lockdown is the focus on a state/district-oriented cluster containment strategy. All “Red Zones” Remain under strict lockdown, whereas several relaxations of measures are permitted in orange and green zones[25] . The risk assessment of the zones happens weekly.

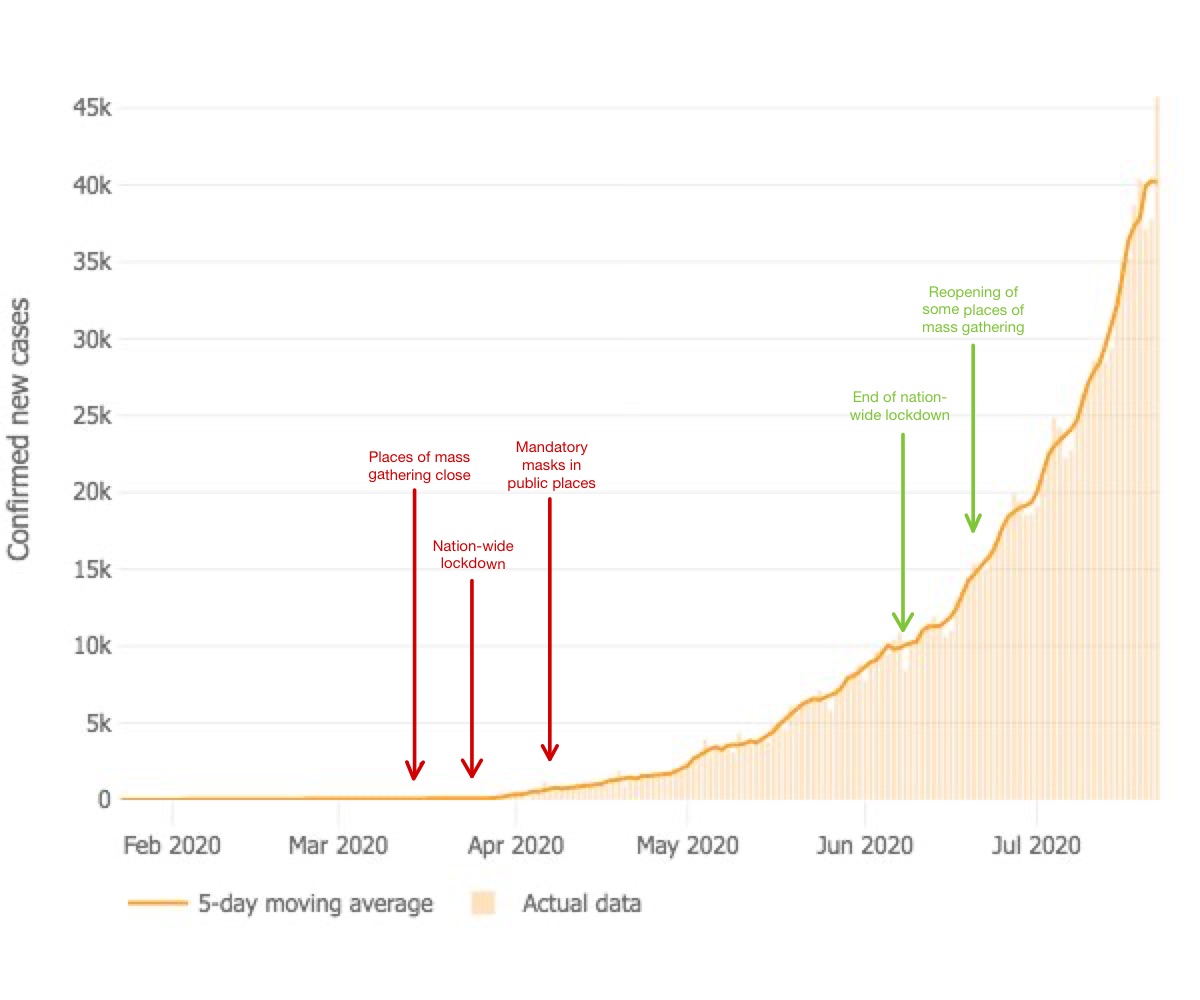

3.4 Timing of the Measures

In the following graph I tried to illustrate the timing of key measures in relation to the daily confirmed new cases. Restrictions are marked with red arrows and relaxations of measures are marked with green arrows. One can see that at the beginning measures were imposed while the daily number of new cases was still rather low. As the number of confirmed new cases rose, however, the nation wide restictions were greatly relaxed, which seems rather paradoxical.

3.5 Aarogya Setu App

On April 2nd, India launched the Aarogya Setu App, which enables Bluetooth based contact tracing, a mapping of potential hotspots and the spread of valid information about COVID 19 [26] . Privacy, security and transparency are the key pillars of the app. To ensure transparency, the source code for the app is available online and open for review and collaboration to improve the app. At the end of May 114 million users had downloaded the app and more than 3,500 hotspots have been identified [27] . Other countries have also developed Apps for contact tracing, for example Chile, Taiwan and Netherlands.

Cases per State

3.6 Coordination across levels

India is defined as a “Union of States” in Article 1 of the Constitution [28] . Currently there are 28 state and 8 union territories in India, each wich administrative, legislative and judicial power (Kumar, 2014). However, the federal system is not based on equality between the union and the states/union territories, as the central government of India has the power to deeply invade the states’ legislative and executive powers (Kumar, 2014). Furthermore, there is no effective mechanism for a coordination of aggregated interest of the states versus the central government (Kumar, 2014).

The Epidemic Disease Act permits the states to implement state-specific measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic [29] . India is an extremely diverse country with dissimilar geographies and demographics. Futhermore, like in Norway, the case loads between the states in India also differes greatly. Therefore, a state-specific response is essential for an effective containment of the virus. To guarantee an operative coordination between the center and the states during the epidemic “Nodal Officers” were designated by each state to work together with various national Ministries [30] . Innovate and resourceful initiatives driven by local actors have shown great success. The state of Kerala is of the successful crisis management stories that have also received international attention.

Kerala

Kerala is located in southwestern India and has a population of approximately 35 Million [31] . The first cases of Covid-19 were reported in Kerala. However, the Government of Kerala had stated to prepare before the first case was confirmed, and “had already released coronavirus-specific guidelines that established case definitions, screening and sampling protocol, hospital preparedness and surveillance” [32] . The State Disaster Management Committee convened for regular meetings and daily press briefings were held by the Kerala Health Minister [33] . Social Distancing measures and contact-tracing were being used to prevent the spreading of the virus in the state before nation-wide measures were implemented [34]

The Government of Kerala defined three main areas of focus for the COVID-19 strategy: Effective risk communication, a community-based approach and social welfare policies [35] . Communication channels were created to spread valid information about the Virus and eliminate fake news. The community was engaged through the possibility to volunteer as helpers and through the creation of community-based on ground surveillance. The Government of Kerala also ensured the social and economic protection of vulnerable communities with the help of extensive economic relief-packages.

Furthermore, WHO consultants have been deployed in Kerala to support the rapid response teams (RRT) in decision-making, risk-assessment and case-detection [36] . The Governor of Kerala, Shri Arif Mohammed Khan, also encouraged retired doctors and medicine students to enlist with the State Government to volunteer with their services and motivated over 300 psychologists to advise people in quarantine on mental health issues [37] . The sucess of the pro-active approach in Kerala has been praised and could function as an example for other states to follow.

The Epidemic Disease Act permits the states to implement state-specific measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic [29] . India is an extremely diverse country with dissimilar geographies and demographics. Futhermore, like in Norway, the case loads between the states in India also differes greatly. Therefore, a state-specific response is essential for an effective containment of the virus. To guarantee an operative coordination between the center and the states during the epidemic “Nodal Officers” were designated by each state to work together with various national Ministries [30] . Innovate and resourceful initiatives driven by local actors have shown great success. The state of Kerala is of the successful crisis management stories that have also received international attention.

Kerala

Kerala is located in southwestern India and has a population of approximately 35 Million [31] . The first cases of Covid-19 were reported in Kerala. However, the Government of Kerala had stated to prepare before the first case was confirmed, and “had already released coronavirus-specific guidelines that established case definitions, screening and sampling protocol, hospital preparedness and surveillance” [32] . The State Disaster Management Committee convened for regular meetings and daily press briefings were held by the Kerala Health Minister [33] . Social Distancing measures and contact-tracing were being used to prevent the spreading of the virus in the state before nation-wide measures were implemented [34]

The Government of Kerala defined three main areas of focus for the COVID-19 strategy: Effective risk communication, a community-based approach and social welfare policies [35] . Communication channels were created to spread valid information about the Virus and eliminate fake news. The community was engaged through the possibility to volunteer as helpers and through the creation of community-based on ground surveillance. The Government of Kerala also ensured the social and economic protection of vulnerable communities with the help of extensive economic relief-packages.

Furthermore, WHO consultants have been deployed in Kerala to support the rapid response teams (RRT) in decision-making, risk-assessment and case-detection [36] . The Governor of Kerala, Shri Arif Mohammed Khan, also encouraged retired doctors and medicine students to enlist with the State Government to volunteer with their services and motivated over 300 psychologists to advise people in quarantine on mental health issues [37] . The sucess of the pro-active approach in Kerala has been praised and could function as an example for other states to follow.

3.7 Evaluation of Decision Making

A conflict between an upward shift in decision making vs. decentralised decision making often occurs during a crisis (Boin et al, 2017). In India, the central government makes key decisions and provides general guidelines, however, states can make stricter rules within the provided framework of the central government.

During the crisis special committees and rapid response teams were created in India. The formation of new teams in turbulent conditions under high pressure have potential dangers (Boin et al, 2017).“New Group Syndrome”, which is a result of uncertain roles and status, and “Group Think”, as a result of excessive concurrence seeking, can both lead to the concealing of vital opinions that do not align with the leadership and can thus have detrimental consequences (Boin et al, 2017). I could not find information about how the Indian government counters these potential dangers, for example, through ensuring diversity within the teams.

Improvisation during a crisis is vital and in the so called crisis improvisation mode “rules can be set up to facilitate a switch to improvisation under certain specific circumstances” (Boin et al., 2017, p. 62). When the corona crisis was declared a notified disaster in India in early March [38] the government could to some extent make use of improvisation and for example allocate special funds flexibly. Furthermore, I could identify signs of pragmatic crisis response in India. Especially, the concept of bricolage, which means improvising with the available resources (Ansell & Boin, 2019) can be observed in Kerala.

During the crisis special committees and rapid response teams were created in India. The formation of new teams in turbulent conditions under high pressure have potential dangers (Boin et al, 2017).“New Group Syndrome”, which is a result of uncertain roles and status, and “Group Think”, as a result of excessive concurrence seeking, can both lead to the concealing of vital opinions that do not align with the leadership and can thus have detrimental consequences (Boin et al, 2017). I could not find information about how the Indian government counters these potential dangers, for example, through ensuring diversity within the teams.

Improvisation during a crisis is vital and in the so called crisis improvisation mode “rules can be set up to facilitate a switch to improvisation under certain specific circumstances” (Boin et al., 2017, p. 62). When the corona crisis was declared a notified disaster in India in early March [38] the government could to some extent make use of improvisation and for example allocate special funds flexibly. Furthermore, I could identify signs of pragmatic crisis response in India. Especially, the concept of bricolage, which means improvising with the available resources (Ansell & Boin, 2019) can be observed in Kerala.

4 Meaning Making

Meaning making means that the government is "offering a situational definition and narrative, that is convincing, helpful, and inspiring to citizens and responders" (Boin et al., 2020, p.15). In the following section I will examine how the government of India framed the crisis, how uncertainty was communicated and give an overview on the risk communication and awareness campaigns.

4.1 Framing of the Crisis

The moment that leaders define an issue as a crisis is crucial in crafting a frame (Boin et al., 2020). On the 14th of March, the Government of India declared the Coronavirus epidemic a “notified disaster” [39] . Buznan et al. describe the concept of defining an issue as a crisis as securitization. They explain the process of securitization as “an issue is dramatized and presented as an issue of supreme priority; thus, by labelling it as security, an agent claims a need for and a right to treat it by extraordinary means.” (Buznan et al, 1998, p.26) By defining the epidemic as a notified disaster, the government of India is justifying strict measures and the transferal of power to the centre.

The Prime Minister Modi uses metaphoric language in his speeches and for example has stated "I understand your troubles but there was no other way to wage war against coronavirus. It is a battle of life and death and we have to win it.” [40] . He is crafting a certain frame by comparing the crisis to a “war” and thus alluding to the seriousness of the situation. Similar war-like language was used by the president in France.

Other recurring themes in Modi’s speeches are unity and light/darkness. When he announced the 9 minutes of solidarity on April 5th he said "We must move towards the light. We must take the ones who are affected the most -- the ones with less resources -- towards hope. We must move past the darkness and uncertainty that has been created, and go towards the light. We must spread the light everywhere.” [41] He is creating a frame of a united country and in his speeches and communicates that everyone, including the most vulnerable parts of the population, are considered in the crisis management.

The Government of India is not transparent about uncertainties of the crisis. I could for example not find information about the process of data collection of case numbers the websites of national ministries.

The Prime Minister Modi uses metaphoric language in his speeches and for example has stated "I understand your troubles but there was no other way to wage war against coronavirus. It is a battle of life and death and we have to win it.” [40] . He is crafting a certain frame by comparing the crisis to a “war” and thus alluding to the seriousness of the situation. Similar war-like language was used by the president in France.

Other recurring themes in Modi’s speeches are unity and light/darkness. When he announced the 9 minutes of solidarity on April 5th he said "We must move towards the light. We must take the ones who are affected the most -- the ones with less resources -- towards hope. We must move past the darkness and uncertainty that has been created, and go towards the light. We must spread the light everywhere.” [41] He is creating a frame of a united country and in his speeches and communicates that everyone, including the most vulnerable parts of the population, are considered in the crisis management.

The Government of India is not transparent about uncertainties of the crisis. I could for example not find information about the process of data collection of case numbers the websites of national ministries.

4.2 Risk Communication and Awareness Campaigns

The National Disaster Management Guidelines as well as the Cluster Containment Strategy emphasise the importance of risk communication and awareness campaigns. The Government of India has an extensive traditional and social media presence.

One can find daily updates on active cases, recoveries and deaths on the Website of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. There are also various flyers and illustrations which display appropriate behaviour or provide basic information on COVID-19. For example the "Dos and Don’ts" or an “Illustrative Guide on COVID Appropriate Behaviour”. This kind of information material is also appropriate for illiterate people or children. Furthermore, the MoHFW is committed to fighting stigma related to COVID-19 and for example has published a Guide to address stigma.

The Press Information Bureau publishes a Bulletin on COVID 19 on a daily basis. The real-time interactive platform for citizens “COVID India Seva" was created to enable transparent e-governance and deliver real time information and answer questions[42] . Furthermore the National Disaster Management Authority publishes all new guidelines, advisories and plans connected to the COVID-19 epidemic on their website.

The Government of India also uses various social media channels to spread valid information about the Coronavirus and give tips on appropriate behaviour. For example Youtube Videos like “Steps to maintain mental health and wellbeing during lockdown” . There are also toll-free hotlines for example for information (011-23978046) or for psycho-social support (080-46110007).

Through the extensive online presence a large share of the population can be reached, however, it is difficult to asses to what extent the information reaches people who live in rather isolated villages and do not have access to newspaper, radio, television or the internet.

One can find daily updates on active cases, recoveries and deaths on the Website of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. There are also various flyers and illustrations which display appropriate behaviour or provide basic information on COVID-19. For example the "Dos and Don’ts" or an “Illustrative Guide on COVID Appropriate Behaviour”. This kind of information material is also appropriate for illiterate people or children. Furthermore, the MoHFW is committed to fighting stigma related to COVID-19 and for example has published a Guide to address stigma.

The Press Information Bureau publishes a Bulletin on COVID 19 on a daily basis. The real-time interactive platform for citizens “COVID India Seva" was created to enable transparent e-governance and deliver real time information and answer questions[42] . Furthermore the National Disaster Management Authority publishes all new guidelines, advisories and plans connected to the COVID-19 epidemic on their website.

The Government of India also uses various social media channels to spread valid information about the Coronavirus and give tips on appropriate behaviour. For example Youtube Videos like “Steps to maintain mental health and wellbeing during lockdown” . There are also toll-free hotlines for example for information (011-23978046) or for psycho-social support (080-46110007).

Through the extensive online presence a large share of the population can be reached, however, it is difficult to asses to what extent the information reaches people who live in rather isolated villages and do not have access to newspaper, radio, television or the internet.

4.3 Evaluation of Meaning Making

In effective crisis management a coherent social media strategy in necessary and the government should be proactive in monitoring and dismantling the spread of false information (Boin et al., 2020 ). The Indian government performs well in this category and also uses a decentralised form of coordination of outgoing information, which Boin et al. (2020) suggest. However, this sometimes leads to contradicting information from different governmental sources, possibly causing confusion. I could not find general (social) media guidelines, which could further improve the media presence of the Indian governmental institutions.

Furthermore, I noticed that the Government of India is masking certain parts of the crisis management. Masking means “not telling the full story (…) obscuring sensitive aspects of their own crisis response operations” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 92). The dire situation of the migrant workers and in slums are for example not addressed. Various sources also claim that the Prime Minister and his party have made efforts to repress critical voices in order to strengthen their own image during the pandemic [43] . The rally-around-the-flag effect provides leaders the opportunity to frame the crisis and consequently to gain support during a crisis (Boin et al., 2020). However, this window of opportunity should not be misused, otherwise it could lead to diminishing legitimacy and trust in the government after the crisis.

Furthermore, I noticed that the Government of India is masking certain parts of the crisis management. Masking means “not telling the full story (…) obscuring sensitive aspects of their own crisis response operations” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 92). The dire situation of the migrant workers and in slums are for example not addressed. Various sources also claim that the Prime Minister and his party have made efforts to repress critical voices in order to strengthen their own image during the pandemic [43] . The rally-around-the-flag effect provides leaders the opportunity to frame the crisis and consequently to gain support during a crisis (Boin et al., 2020). However, this window of opportunity should not be misused, otherwise it could lead to diminishing legitimacy and trust in the government after the crisis.

5 Legitimacy

Governance legitimacy is defined as “the relationship between government authorities and citizens and concerns citizens’ perception of whether the action of the authorities are desirable, proper or appropriate within a certain socially constructed system of norms, values and beliefs" (Christensen et al, 2019, p7). In the following section I will analyse how the public is regarding and reacting to the rules imposed by the Indian government, using data from the international research data and analytics group YouGov, and evaluate what implications the results may have.

Social distancing can be regarded as a collective action problem and modelled in a game-theoretic approach in order to unterstand the strategic interactions amongst the population. What is interesting is that in India people have been rather compliant with the social distancing rules imposed by the government and even adhered to stricter self-imposed rules [44] . However, social distancing in India is a privilege and a substantive part of the population, for example people who live in slums or the migrant workers, simply do not have the resources to adhere to all restrictions.

Social distancing can be regarded as a collective action problem and modelled in a game-theoretic approach in order to unterstand the strategic interactions amongst the population. What is interesting is that in India people have been rather compliant with the social distancing rules imposed by the government and even adhered to stricter self-imposed rules [44] . However, social distancing in India is a privilege and a substantive part of the population, for example people who live in slums or the migrant workers, simply do not have the resources to adhere to all restrictions.

5.1 Government Handling

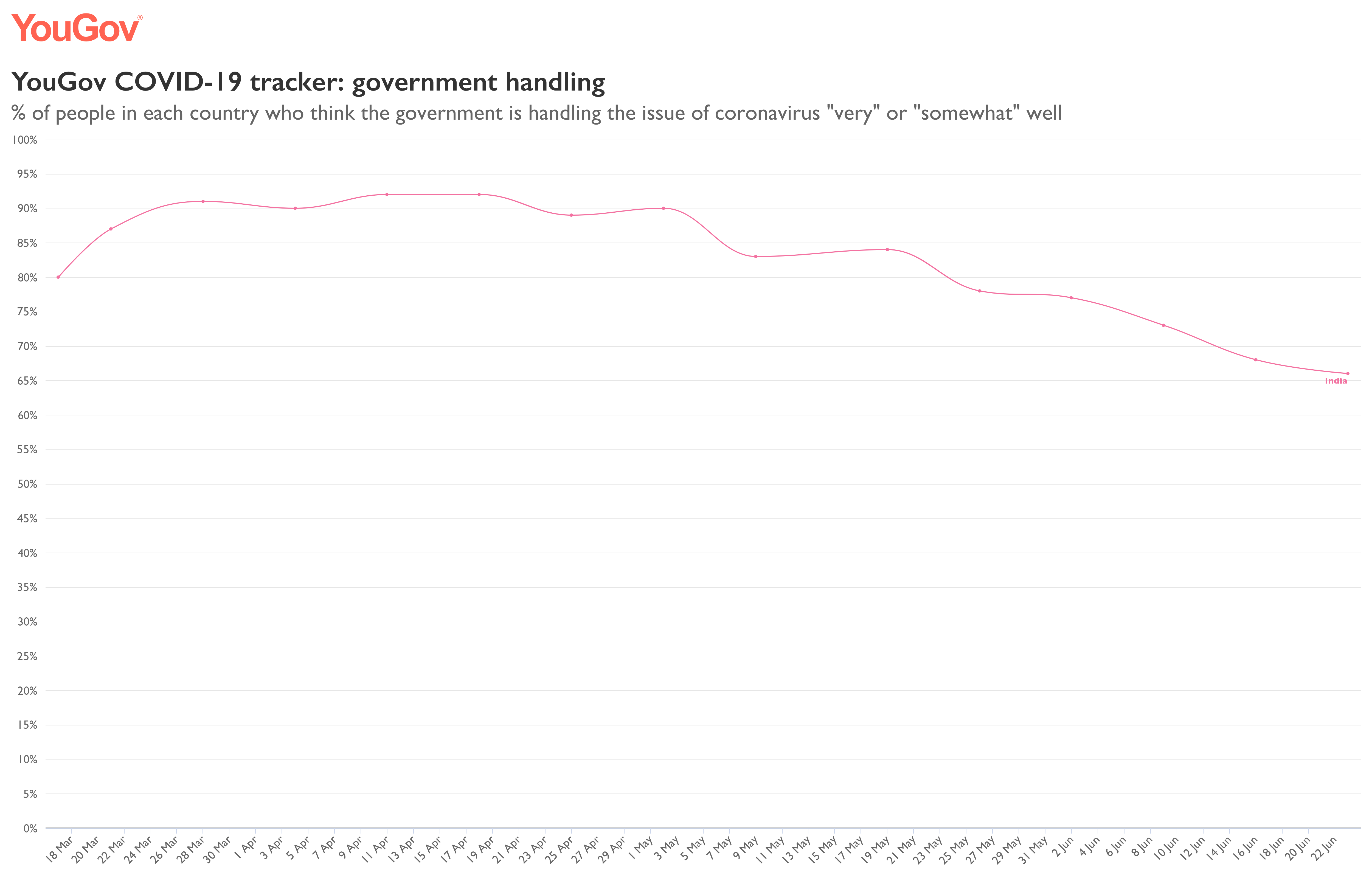

When one looks at the change of the percentage of people in India who think that the government is handling the issue of coronavirus “very” or “somewhat” well, it is interesting to note that the overall approval rates are always above 50% [45] . An increase in support of the government handling can be seen in late March. This is the time that the nation wide lockdown started, indicating that the population in general viewed this as a legitimate measure. The approval rates have decreased again after the end of the nation wide lockdown, which could be explained by the exponentially rising case-numbers despite the governmental restrictions.

5.2 Trust in health authorities

Another interesting indicator for legitimacy is the confidence in health authorities to respond to the coronavirus. The percentage of people in India who have “a lot” or a “fair amount” of confidence in the health authorities rose when the nation wide lockdown was imposed and remained relatively constant between 80-90% until the beginning of May [46] . The confidence in health authorities has since dropped significantly and is now below 65%. The drop can probably be explained with a similar logic as the drop of approval rates of government handling.

5.3 Perceived National Improvement

Striking is the high approval rate of government measures and relatively high trust in public health authorities when simultaneously the perceived national improvement is significantly lower. At the beginning of May, while the nation-wide lockdown was still enforced, approximately 41 % of the questioned population in India thought that coronavirus is getting better in India [47] . In early June, however, only around 21% saw an improvement. It is seemly paradoxical that although a large share of the population does not think that the coronavirus situation is improving, still believe that the government is handling the crisis well. Perhaps this could be due to a strong party identification with the currently ruling “Bharatiya Janata Party” and support of measures despite detrimental consequences.

5.4 Evaluation of Legitimacy

It is questionable whether the results of the survey are completely unbiased, because people who are gravely affected by the crisis and are not receiving enough governmental support, such as people who live in slums, were probably not included in the sample. Therefore, one must be careful when interpreting the results and keep in mind that the support for government actions and trust in public health authorities is could potentially be overestimated.

6 Overall Evaluation

In this Wiki I examined the state of preparedness of India before the crisis, by looking at existing disaster management plans, the health system and other indicators and then took a closer step at the first tasks of crisis management: sense-making, decision-making, meaning-making and legitimacy. The fifth step would be learning, however, due to the ongoing nature of the crisis, it was too early to evaluate this point. Since I already evaluated each step separately, I decided to come back to the three components - threat, urgency and uncertainty - that are used by Boin et al. (2017) to define a crisis, in my overall evaluation.

Threat

During the COVID-19 pandemic core values, especially safety, security and health were threatened. Although disaster management plans and guidelines exist in India, there is a lot of room for improvement of preparedness for pandemics. Especially, the underfunding of the health system and the unequal access to healthcare make the threat of the COVID 19 pandemic even more severe in India.

Urgency

Urgency is not an inherent attribute of a crisis, but rather socially constructed and is therefore closely linked to one’s proximity to the crisis (Boin et al, 2017). The number of new confirmed cases is continuously rising in India making the crisis urgent, however, due to the uneven distribution of cases across the country, the perception of urgency may vary in different states. The Indian government framed the crisis as urgent by labelling it as a disaster and through the use of war-like language. The urgency is also reflected in the quick decision making by some state governments such as in Kerala.

Uncertainty

Although the testing capacities were ramped up, the number of tests that are being conducted in India is still comparatively low, causing a high degree of uncertainty concerning the real spread of the virus and potential consequences. The uncertainty of the situation is, however, not really being transparently communicated.

Overall, one could say that (from looking at the case until the end of July) India is still in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is characterised by threat, urgency and a high degree of uncertainty. It is unclear how the pandemic will continue to unfold and what the societal, political and economic consequences will be. It will be interesting to continue to examine how the Indian national government and the state governments manage the crisis and whether the existing strategies will suffice to contain the virus or whether new perhaps improvised and pragmatic approaches will be necessary to manage the crisis successfully .

Threat

During the COVID-19 pandemic core values, especially safety, security and health were threatened. Although disaster management plans and guidelines exist in India, there is a lot of room for improvement of preparedness for pandemics. Especially, the underfunding of the health system and the unequal access to healthcare make the threat of the COVID 19 pandemic even more severe in India.

Urgency

Urgency is not an inherent attribute of a crisis, but rather socially constructed and is therefore closely linked to one’s proximity to the crisis (Boin et al, 2017). The number of new confirmed cases is continuously rising in India making the crisis urgent, however, due to the uneven distribution of cases across the country, the perception of urgency may vary in different states. The Indian government framed the crisis as urgent by labelling it as a disaster and through the use of war-like language. The urgency is also reflected in the quick decision making by some state governments such as in Kerala.

Uncertainty

Although the testing capacities were ramped up, the number of tests that are being conducted in India is still comparatively low, causing a high degree of uncertainty concerning the real spread of the virus and potential consequences. The uncertainty of the situation is, however, not really being transparently communicated.

Overall, one could say that (from looking at the case until the end of July) India is still in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is characterised by threat, urgency and a high degree of uncertainty. It is unclear how the pandemic will continue to unfold and what the societal, political and economic consequences will be. It will be interesting to continue to examine how the Indian national government and the state governments manage the crisis and whether the existing strategies will suffice to contain the virus or whether new perhaps improvised and pragmatic approaches will be necessary to manage the crisis successfully .

7 Favorite stay at home song

8 Works Cited

Ansell, C., & Boin, A. (2019). Taming deep uncertainty: The potential of pragmatist principles for understanding and improving strategic crisis management. Administration & Society, 51(7), 1079–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399717747655

Boin, A., 't Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2017). The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership under Pressure (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339756

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Rienner.

Chokshi, M., Patil, B., Khanna, R., Neogi, S. B., Sharma, J., Paul, V. K., & Zodpey, S. (2016). Health systems in India. Journal of Perinatology, 36(S3), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.184

Christensen, T., Lægreid, P., & Rykkja, L. H. (2019). Societal security and crisis management: Governance capacity and legitimacy. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92303-1

Keller, A. C., Ansell, C. K., Reingold, A. L., Bourrier, M., Hunter, M. D., Burrowes, S., & MacPhail, T. M. (2012). Improving pandemic response: A sensemaking perspective on the spring 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 3(2), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/1944-4079.1101

Kumar, A. (2015). Indian urban households’ access to basic amenities: Deprivations, disparities and determinants. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research. 9(3), 278–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973801015579754

Kumar, C. (2014). Federalism in India: a critical appraisal. Journal of Business Management and Social Science Research. 3(9), 31–43.

Phua, J., Faruq, M. O., Kulkarni, A. P., Redjeki, I. S., Detleuxay, K., Mendsaikhan, N., Sann, K. K., Shrestha, B. R., Hashmi, M., Palo, J. E. M., Haniffa, R., Wang, C., Hashemian, S. M. R., Konkayev, A., Mat Nor, M. B., Patjanasoontorn, B., Nafees, K. M. K., Ling, L., Nishimura, M., … Fang, W.-F. (2020). Critical care bed capacity in Asian countries and regions: Critical Care Medicine, 48(5), 654–662. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004222

Ps, R. (2016). The Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897: public health relevance in the current scenario. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 1(3), 156-160 https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2016.043

Rhodes, A., Ferdinande, P., Flaatten, H., Guidet, B., Metnitz, P. G., & Moreno, R. P. (2012). The variability of critical care bed numbers in Europe. Intensive Care Medicine, 38(10), 1647–1653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2627-8

Sheikh, K., Saligram, P. S., & Hort, K. (2015). What explains regulatory failure? Analysing the architecture of health care regulation in two Indian states. Health Policy and Planning, 30(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czt095

Sources for the timeline

(1) Ministry of Civil Aviation https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1600015 accessed on 28/06/2020

(2) Indian Council of Medical Research https://covid.icmr.org.in/index.php accessed on 29/06/2020

(3) WHO Situation Report 6 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

(4) Bureau of Immigration https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/VisarestrictionsrelatedtoCOVID19Ministries.pdf (accessed on 28/06/2020)

(5) WHO India Situation Report 7 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

(6) Live Mint https://www.livemint.com/news/india/govt-calls-for-social-distancing-as-confirmed-coronavirus-cases-rise-to-124-11584384445401.html accessed on 28/06/2020

(7) MOHFW https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Traveladvisory.pdf accessed on 28/06/2020

(8) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/ndmaorder240320.pdf accessed on 29/06/2020

(9) Government of India https://www.mygov.in/aarogya-setu-app/ accessed on 25/06/2020

(10) India Today https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/lights-off-electricity-on-power-ministry-releases-faqs-on-pm-modi-s-9-pm-9-minutes-call-1663619-2020-04-05 accessed on 15/06/2020

(11) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/NDMA-Order-for-extending-the-Lockdown-Period-till-030520.pdf accessed on 29/96/2020

(12) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/MoHFW-Letter-States-reg-containment-of-Hotspots.pdf accessed on 28/06/2020

(13) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/NDMA-ORDER-DTD-1.5.20.pdf accessed on 28/06/2020

(14) Press Information Bureau https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1620095 accessed on 29/06/2020

(15) Press Information Bureau https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608009 accessed on 29/06/2020

(16) Indian Express https://indianexpress.com/article/india/lockdown-5-0-guidelines-6434777/ accessed on 29/06/2020

Boin, A., 't Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2017). The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership under Pressure (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339756

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Rienner.

Chokshi, M., Patil, B., Khanna, R., Neogi, S. B., Sharma, J., Paul, V. K., & Zodpey, S. (2016). Health systems in India. Journal of Perinatology, 36(S3), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.184

Christensen, T., Lægreid, P., & Rykkja, L. H. (2019). Societal security and crisis management: Governance capacity and legitimacy. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92303-1

Keller, A. C., Ansell, C. K., Reingold, A. L., Bourrier, M., Hunter, M. D., Burrowes, S., & MacPhail, T. M. (2012). Improving pandemic response: A sensemaking perspective on the spring 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 3(2), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/1944-4079.1101

Kumar, A. (2015). Indian urban households’ access to basic amenities: Deprivations, disparities and determinants. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research. 9(3), 278–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973801015579754

Kumar, C. (2014). Federalism in India: a critical appraisal. Journal of Business Management and Social Science Research. 3(9), 31–43.

Phua, J., Faruq, M. O., Kulkarni, A. P., Redjeki, I. S., Detleuxay, K., Mendsaikhan, N., Sann, K. K., Shrestha, B. R., Hashmi, M., Palo, J. E. M., Haniffa, R., Wang, C., Hashemian, S. M. R., Konkayev, A., Mat Nor, M. B., Patjanasoontorn, B., Nafees, K. M. K., Ling, L., Nishimura, M., … Fang, W.-F. (2020). Critical care bed capacity in Asian countries and regions: Critical Care Medicine, 48(5), 654–662. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004222

Ps, R. (2016). The Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897: public health relevance in the current scenario. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, 1(3), 156-160 https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2016.043

Rhodes, A., Ferdinande, P., Flaatten, H., Guidet, B., Metnitz, P. G., & Moreno, R. P. (2012). The variability of critical care bed numbers in Europe. Intensive Care Medicine, 38(10), 1647–1653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2627-8

Sheikh, K., Saligram, P. S., & Hort, K. (2015). What explains regulatory failure? Analysing the architecture of health care regulation in two Indian states. Health Policy and Planning, 30(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czt095

Sources for the timeline

(1) Ministry of Civil Aviation https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1600015 accessed on 28/06/2020

(2) Indian Council of Medical Research https://covid.icmr.org.in/index.php accessed on 29/06/2020

(3) WHO Situation Report 6 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

(4) Bureau of Immigration https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/VisarestrictionsrelatedtoCOVID19Ministries.pdf (accessed on 28/06/2020)

(5) WHO India Situation Report 7 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

(6) Live Mint https://www.livemint.com/news/india/govt-calls-for-social-distancing-as-confirmed-coronavirus-cases-rise-to-124-11584384445401.html accessed on 28/06/2020

(7) MOHFW https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Traveladvisory.pdf accessed on 28/06/2020

(8) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/ndmaorder240320.pdf accessed on 29/06/2020

(9) Government of India https://www.mygov.in/aarogya-setu-app/ accessed on 25/06/2020

(10) India Today https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/lights-off-electricity-on-power-ministry-releases-faqs-on-pm-modi-s-9-pm-9-minutes-call-1663619-2020-04-05 accessed on 15/06/2020

(11) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/NDMA-Order-for-extending-the-Lockdown-Period-till-030520.pdf accessed on 29/96/2020

(12) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/MoHFW-Letter-States-reg-containment-of-Hotspots.pdf accessed on 28/06/2020

(13) National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/NDMA-ORDER-DTD-1.5.20.pdf accessed on 28/06/2020

(14) Press Information Bureau https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1620095 accessed on 29/06/2020

(15) Press Information Bureau https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608009 accessed on 29/06/2020

(16) Indian Express https://indianexpress.com/article/india/lockdown-5-0-guidelines-6434777/ accessed on 29/06/2020

[1] Tikannen, R., Osborn, R., Mossialos, E., Djordjevic, A., & Wharton, G. International health care system profiles: India. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/india accessed on 05/06/22

[2] World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database. https://apps.who.int/nha/database accessed on 21/05/2020

[3] World Health Organization. Global Health Expenditure Database. https://apps.who.int/nha/database accessed on 21/05/2020

[4] The World Bank. Hospital beds (per 1,000 people). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS accessed on 21/05/2020

[5] The World Bank. Nurses and midwives (per 1,000 people). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.NUMW.P3?end=2015&start=1960&view=chart accessed on 21/05/2020

[6] The World Bank. Physicians (per 1,000 people) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?end=2015&start=1960&view=chart accessed on 21/05/2020

[7] Global Health Security Index. https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf accessed on 18/06/2020

[8] John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. New Cases of COVID-19 In World Countries. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases accessed on 02/07/2020

[9] Government of India https://www.mygov.in/covid-19 accessed on 02/07/2020

[10] Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Cente. Cumulative Cases. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/cumulative-cases accessed on 22/06/2020

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People Who Are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html accessed on 15/05/2020

[12] Statista. Distribution of the population by age group in France. https://www.statista.com/statistics/464032/distribution-population-age-group-france/ accessed on 21/05/2020

[13] Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. How Does Testing in the U.S. Compare to Other Countries? https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/international-comparison accessed on 22/06/2020

[14] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Covid-19 testing - when and how?https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/FINAL_14_03_2020_ENg.pdf accessed on 19/06/2020

[15] WHO India Situation Report 8 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

[16] Indian Council of Medical Research. https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/strategy/New_additional_Advisory_23062020_2.pdf accessed on 25/06/202

[17] Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/positive-rate-daily-smoothed?tab=chart&country=~IND accessed on 03/07/2020

[18] John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/international-comparison accessed on 13/07/2020

[19] Press Information Bureau. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608009 accessed on 29/06/2020

[20] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/3ContainmentPlanforLargeOutbreaksofCOVID19Final.pdf accessed on 29/06/2020

[21] Ministry of Home Affairs https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/MHA%20Order%20Dt.%201.5.2020%20to%20extend%20Lockdown%20period%20for%202%20weeks%20w.e.f.%204.5.2020%20with%20new%20guidelines.pdf Accessed on 29/06/2020

[22] Press Information Bureau https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1620095 accessed on 29/06/2020

[23] Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. How Does Testing in the U.S. Compare to Other Countries? https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/international-comparison accessed on 22/06/2020

[24] Indian Express https://indianexpress.com/article/india/lockdown-5-0-guidelines-6434777/ accessed on 29/06/2020

[25] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/3ContainmentPlanforLargeOutbreaksofCOVID19Final.pdf accessed on 29/06/2020

[26] Government of India https://static.mygov.in/rest/s3fs-public/mygov_159056978751307401.pdf accessed 13/07/2020

[27] Government of India https://static.mygov.in/rest/s3fs-public/mygov_159050700051307401.pdf accessed on 13/07/2020

[28] The Consitution of India https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf accessed on 29/06/2020

[29] The Epidemic Disease Act https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/10469/1/the_epidemic_diseases_act%2C_1897.pdf accessed on 29/06/2020

[30] Ministry of Personnel, Pubic Grievances and Pensions. https://goicharters.nic.in/duties_and_responsibilities_St.htm accessed on 29/06/2020

[31] Kerala Government. https://kerala.gov.in/census2011 accesses 02/07/2020

[32] National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/response-to-covid19-by-kerala.pdf accessed on 02/07/2020

[33] WHO India Situation Report 2 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

[34] WHO India Situation Report 5 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020.

[35] National Disaster Management Authority https://ndma.gov.in/images/covid/response-to-covid19-by-kerala.pdf accessed on 02/07/2020

[36] WHO India Situation Report 2 https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)/india-situation-report accessed on 01/06/2020

[37] Press Information Bureau. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1608549 accessed on 29/06/2020

[38] Live Mint. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/india-declares-coronavirus-outbreak-as-a-notified-disaster-11584184739353.html accessed on 12/07/2020

[39] NDTV India https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/india-declares-coronavirus-a-notified-disaster-lists-compensation-2194915 accessed 02/07/2020

[40] BBC https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52081396 accessed on 02/07/2020

[41] Business Today India. https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/trends/coronavirus-lockdown-pm-modi-asks-indians-to-light-candles-lamps-at-9pm-on-april-5/story/400021.html accessed on 02/07/2020

[42] Press Information Bureau https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1616667 accessed 29/06/2020

[43] The Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/06/23/an-exploding-coronavirus-crisis-shows-modi-is-not-up-task-leading-india/ accessed on 02/07/202

[44] YouGov. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/international/articles-reports/2020/03/17/level-support-actions-governments-could-take accessed on 12/07/2020

[45] YouGov. https://yougov.de/news/2020/06/04/corona-international-unterstutzung-der-regierungsm/ accessed on 03/07/2020

[46] YouGov https://yougov.co.uk/topics/international/articles-reports/2020/03/17/perception-government-handling-covid-19 accessed on 12/07/2020

[47] YouGov https://yougov.de/news/2020/06/04/corona-international-unterstutzung-der-regierungsm/ accessed on 12/07/2020